(paradise) . Sohyong Lee, Rudik Ovsepyan, Danica Ribi, santoni kina, Keywan Tafteh, Tiago Da Cruz. January 25 – March 1, 2025. Group exhibition.

Sohyong Lee. Place, temporary . 2024.

CURRENT

(paradise)

Sohyong Lee, Rudik Ovsepyan, Danica Ribi, santoni kina, Keywan Tafteh, Tiago Da Cruz

Duration: January 25 – March 1, 2025. Winter.

Location: Reisig and Taylor Contemporary (4478 W Adams Blvd, Los Angeles, 90016).

Type: Group Exhibition.

Count: 6.

Announcement: Flyer.

Delirium: (Lenin)graph.

Release: File.

Reference: Checklist.

Population: Bios.

Thermostat: 70 degrees Fahrenheit.

Topology: Preliminary Diagram.

Press: This Week’s Must-See Art (Curate LA: February 20-26, 2025).

*Events:

+ [Release] Friday, February 21, 8pm. Screening of ‘maybe now i won’t be so hungry (chewed clay)’ by santoni kina.

__

Exhibition Images: View.

|

Please contact Emily Reisig with any questions:

gallery@reisigandtaylorcontemporary.com

____

____

(paradise) . January 25 – March 1, 2025. Sohyong Lee, Rudik Ovsepyan, Danica Ribi, santoni kina, Keywan Tafteh, Tiago Da Cruz. Group exhibition.

4478 W Adams Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90016.

_ _

Where is paradise? Or, when is it?

(Who’s there?)

How long does it last?

….

subliminals

Paradise: somewhere surrounded by walls. A “staked-out space.” (Surveilled at its borders.) An image of pleasure?

Ending-up in English: with two parts “para-dise” says something about the building of a wall before it ever became anywhere else. Listen: ‘para-’ says “around,” and ‘-dise’ recalls “building a wall (with sticks).” As something written and said, “paradise” starts by naming the division of one place from another. Something that keeps-in or keeps-out. Like a language. It builds-up (along the surface).

Then—or maybe at the same time—it looks like it was separated (from the rest) for pleasure’s sake: it’s a garden, an orchard, a park…. And once this place’s distance from everyday reality was fixed and religiously fixated it became the main attraction: an Eden, and then the (best version of the) afterlife. And then a tropical island—until, by now, it’s been watered-down into a Timeshare. (In any case, what’s important is that it’s never open to everyone, even to the population already living there.) Paradise is built, constructed, imagined, contained, populated, colonized, marketed, (revealed)…. Remember: there are usually Just 10 Easy Steps to Get into Paradise.

When given all the bells this word (paradise) rings, and the Missionary position of this exhibition ‘out West,’ it initially seems unlikely to break-off any question of “paradise” from constructions and imaginations of an afterlife. Or to forget all the advertisements for a tropical “paradise” where heaven is already a place on earth (…it helps if you sing it). Either way: they are both high-end consumer products that are all inherited or stolen in shared imperial schemes. Either way: vacation or salvation—what’s at stake is a body: death or pleasure. Or both. Without the threat of its loss or lack, and without its promise of a beyond, a paradise couldn’t be linked. A life to more life.

But can’t we replace this shiny gold link (of religion and real-estate) with any reæl that records a lifetime and its disappearance or re-memory? With anything that links or loops life to more life? Any strung-out connections tracing a body’s crossing between distant systems and sequences of time? Any secluded, intimate space—any (pleasurable) point of contact between tangled bodies—that leaks over their horizons to another place in time?

First, I have to ask about the function of death or disappearance or a point-of-no-return in relation to ways of surviving: as a crossing from one life into ‘the next’ (or maybe even crossing between two deaths). However, even though it is a way of survival, it is also the opposite of ‘surviving’: an afterlife is a lifeform that occurs exactly when life stops, not when it continues. A kind of discontinuous continuity. So, instead of an aftermath or destination, an afterlife is sought as a recurring medium or exchange between past and future versions or moments that are happening simultaneously. A bodily time that exceeds any individual limits.

Somewhere I go beyond me. Or, somewhere built beyond me that contains me. (You?) Bigger than me but still part of the same picture. It’s something that’s looked at, looked for: sought after. I want it. I need to see it.

A paradise is what’s in me more than me. In bits, pieces. In fits, starts. (Enough to save some for later.)

Are you looking yet?

….

Big Picture-in-Picture

In Los Angeles, in a City of Angels, in the land of la la (la), it would be awfully shy not to say or ask something about ‘paradise’ since it always seems to be here already—if only as a kind of threat or accusation: “you live in paradise you know….”ⁱ (Some do; but most lives mark where paradise is probably designed to stop.) After all, there’s nearly seasonless sunshine that suspends all the realities that spot somewhere real or more possible—somewhere not-paradise. Until it burns. (Until now.ⁱⁱ ) Until the air is soot. But then at least there isn’t any rain…. Until there’s too much and it takes everything with it. Spotless. Still, for the most part, all the water stays right in the ocean. Contained. Until a tsunami. Perfect. Rays, waves, quakes, and flames. (This paradise almost sounds like hell.) Now there’s a fine line between paradise and perpetual damnation. (We knew that already.ⁱⁱⁱ) It all just comes down to proximities and limits. And watching multiple channels: Picture-in-Picture.

So, it looks like (a) paradise is a place after all. And in terms of where, I may as well say it’s right here. Really, though, it’s always somewhere else, never right here. Or, if we are there then we are somewhere luxurious without toil and discomfort; we are on vacation; we don’t need to work; the sex is great—we aren’t really anywhere because we don’t have to be.ⁱᵛ A carnal excess replaces a bodily scarcity. Nothing is lacking, only left behind.

That’s why paradise tends to take place in the afterlife. (From there it becomes a metaphor or figure of speech for some (sub)tropical vacationland, somewhere unreal and away from demands. Or maybe it’s the other way around: earthly, then heavenly?) Because it’s as much a when as a where. A life after death—a way of surviving after life. An ‘after,’ a ‘then,’ or a ‘next.’ It happens once we leave a body and all of its demands behind: buried, burnt; discarded—or, like Lenin, a little moldy but immaculately preserved to the point where a person becomes a place. No need, but some desire remains; in fact, that seems to be the heart of the matter: paradise is placed where we get anything we want while dealing with nothing we dislike. What we leave behind lasts forever, if we want.

Including other people. It seems we are almost never seen alone in the afterlife. Most often, depictions of an afterlife—whether of paradise or its loss—are populated: there are others, strangers and relatives (often alongside splendid clothing, foods, animals, and objects). Whether I am looking at an ancient Egyptian mural or Giovanni di Paolo’s Paradise (1445), a fresco of Ulysses in the Underworld (1st BC), or The Prophet Muhammad’s Ascent to Heaven from the Khamsa by Nizami, the place looks crammed-full of bodies. (Beyond this etymological “paradise,” the population of an afterlife or some kind of ‘higher state’ of consciousness still seems to hold elsewhere; for example, see Gathering of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas (550-577 AD).) Paradise is an intimate space.

But is an afterlife only an image?

These presentations of an afterlife retain something corporeal: a body dies but its image both continues and remains in a supernatural state. This populated vision is equally evident in non-pictorial presentations of divine realms: there is an intricate and complex formation of patterns like scriptive writing, woven textile, geometric tessellation. There is structure. Look at the 8 doors of Jannahᵛ, ornately inscribed architectural entryways into Paradise that provide a material bridge between here/after. Or, for a contemporary example that counters the imperial conquest of the Americas by the Euro-Abrahamics (while still sharing a similar constructedness), see Life after Death by Elias Not Afraid (2022). (And even when tending toward a flowing, serenely natural landscape like in Paolo’s Paradise, there is still a sophisticated architecture in the tapestry-like composition of the figures and scenery forming the image.) Life after death, or life after life (paradise), is somewhere that is constructed, imagined, developed (with all the signature traits of civilization still abounding).

It runs the risk—if not already running the program—of being another Manifest Destiny, another colonial dreamscape that looks something like The Tempest: isolated and away, but with all the worldly social, political, and physical structures still intact. Like Caliban, someone can be there while still being kept outside. That’s what makes it paradise, the near distance from someone else’s suffering. Someone needs to be excluded (while you watch).

Just take a second to see where all the mentioned works are stored: the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, The MET, the Smithsonian, the Vatican, the Harvard Museum of Art… paradise is built for who? Or, at least who gets to keep it? All these proper Names and their property. Royalty, the (Holy) Empire, retains its possession and position at the highest order in the Kingdom. The afterlife is colonized. Buy, sell; submit. Store.

But if an afterlife (paradise) is already built and bought, it is more of a material medium, a physical state—or a kind of subliminal exchange—rather than a palm-pocked destination or a celestial city. It’s a kind of realtime that builds-up in distances between a body and the limits, images, informations, imprints, mementos, processes, markets, screens, and systems that record and regulate somebody’s life and death (like a border crossing). Shaped like the hole a body leaves behind—or where it is placed. Shaped the way memory is molded into visions, things, residues: it falls away.

So where does it all go? Light, memory, history, data, trauma, are all ambiguously stored by body, but what happens when they leave a body behind? Or, in the other direction, what happens when a body leaves them behind?

To some extent a body holds life and death apart, and, as it gives way to gravity, more and more structures emerge in its wake: languages, photographs, archives, museums, genomes, hard-drives, cemeteries. These structures turn decay into a way of life. However, like any paradise not lost, but found (taken) and kept, they are potentially reduced to a commodity among commodities through extractive colonial enterprises that feed the living (Bios), and keep-up the good life, by repeatedly draining the dead (Necros) of their (after)life.

Anyway, all this vertigo of the cadaver ends-up seeming more morbid than paradise should be. What is hopeful about paradise is that since it is something constructed it can be destroyed and rebuilt. Maybe this time it will be made for others, rather than being a way of keeping everyone else out. After all, like the hole made for the body, paradise only makes room.

….

Just 10 Easy Steps to Get into Paradise

To avoid or address this structural problem I need to see how it came to be constructed in the first place.

I need to go-back to what paradise left behind. If I start at the beginning, if I follow the length of the letters until the word dissolves into primordial parts, I end-up with a kind of architecture or strategy: literally, a “walled” area or enclosure. From Proto-Indo-European roots to a borrowed French term, the ‘para-’ part circulates through several linguistic generations of saying something like “around,” while the ‘-dise’ part arrives along the same tracks for saying something like “(to build (or form with sticks) a) wall” or “walled” or “walling.” Paradise: a walled place. In its initial pass, “paradise” signaled something of the building a wall and the formation of a separation or division between one place and another, seemingly for protective or defensive measures. A place of exemption and a state of exception. (There is, linguistically, a wall, a border; and maybe a gate.) But it is was separated for pleasure’s sake.

A pleasure principle emerges. As it continued to circulate, the idealized, beatified connotation of this term was elaborated and reinforced. In Assyrian (6th/5th BC), it referred to a garden; in Greek (4th BC), a royal park (described as being populated with animals in the Anabasis); in Hebrew (2nd/1st BC), an orchard—and a garden (again), this time with specific reference to the Garden of Eden. It is with the arrival at Eden that the temporality of “paradise” turns towards a mythological origin, a place irretrievably in the past, rather than remaining a present mode of construction. But if Eden is still supposed to be on earth, when did paradise become so celestial, so far away? After all, the fall from paradise doesn’t entirely disjoin life from everlasting life, it just makes mortal life miserable and puts hell on earth with a serpentine Satan now in the mix. An absolute other that’s just like us—or at least we want the same things.

Paradise as an elsewhere—a future (for the dead)—and not just as a before, only comes in after the fact as a way of making life worth living well. (Like a carrot-shaped stick, the keys are dangling in front of the infant….) Instead of being before life, it now takes place after death and after life. Paradise actually predates the afterlife. The timing displaces the location. Either way, whether a where or a when, what remains is a structure and a territory—an exclusive place or timeframe that is cut-off and staked-out. An enclosed, sometimes idealized space made of walls.

Paradise is starting to sound a lot like a gallery.

Or at least like a room—room is made, something is stored and protected. Something that stores and protects like a body while leaving a body behind. In any way, a life is multiplied or extended once it is divided from a body. A paradox: my body produces the afterlife, but I’m told my body prevents my paradise (how Eve that is…).

Meanwhile, I don’t want to get too caught-up in any particular tradition despite the historical timeline of the word and its generations. Ultimately and initially, this exhibition is working-through de-imaginations, deterritorializations, and deconstructions of the “paradise” I have just passed-through. Avoiding the one-way teleology or the one-lane Abrahamic highway to heaven, this exhibition is seeking a sense of a place that is formed ‘after’ a body in both past (, present,) and future at the same time. I am asking how—logically and aesthetically—paradise (as I say it and write right now) is built and how it functions to structure relations between bodies and their remains—how it demonstrates distortions of time and space along a body’s processes, permutations, and dysfunctions.

How is the place of paradise, as an enjoyable afterlife, constructed? Where—or when—is an afterlife and how is it actively made or rendered rather than imagined or awarded? Is it an individual path or a collective (and public) place? What are the architectures of an afterlife? How is a life stored (by a body)? And where does life go if (or when) it leaves a body?

Maybe, when considered in terms of time, a body is ambiguously both a living organism and a kind of database of traces, with no immediate distinction made between “physical” remains and vestigial records. (A body’s timing mediates the boundary of the afterlife: Is the dead body the one in the tomb or the name written on the grave? Is a body limited by flesh or does it spill into different forms? (Grandma’s (body is) gone, did she go to Heaven?))

Like an archive or a scab, which record a past (event, trauma, image, information) while preserving and transforming a body for a future or a ‘somewhere else.’ For sur-survival. But a body is more than an archive and more than a scab (at least until it’s picked). A body enjoys itself.

Just like the little paradise of successfully picking a scab and finding a material release from my body, I am wondering what kinds of enjoyment, what forms of desire, can be actualized by afterlives. Is paradise bound to be bittersweet?

And, still, where is paradise? When is it? Is it after life? After death? Is it between life and death? Between two lives? Or between two deaths? (Between your death and mine: Picture-in-picture?)

Maybe paradise isn’t where I go—maybe it’s all the fragments that populate me once I’m gone. (As long as you enjoy them.)

It’s for you.

“This world divided into compartments, this world cut in two is inhabited by two different species. The originality of the colonial context is that economic reality, inequality, and the immense difference of ways of life never come to mask the human reality. When we examine at close quarters the colonial context, it is evident that what parcels out the world is to begin with the fact of belonging to or not belonging to a given race, a given species. In the colonies the economic substructure is also superstructure. The cause is the consequence; you are rich because you are white, you are white because you are rich. This is why Marxist analysis should always be slightly stretched every time we have to do with the colonial problem.”

—Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth

[—80. (v1.p0.)]

___________________________________

[i] When I first moved to Los Angeles one of my first encounters was with a sun-cooked boomer at a gas station who told me “Welcome to Paradise.” And at the gallery’s first location there was a vinyl decal spelling Paradise on the window (and apparently it had been there for some time…). So maybe this connection to paradise is a little personal. But that’s a good enough place to start.

[ii] Since January 07, 2025, with the start of the Palisades and Eaton fires (and, at the time of publishing this on January 23, 2025, also the Hughes fire), Los Angeles County has been experiencing some of the most intense and (economically and mortally) costly wildfires in the region’s history.

[iii] The European colonization of the Americas is a clear vision of how paradise and hell occur through a simultaneous construction that requires the demonization and absolute exclusion of a (colonially dehumanized) other.

[iv] Or, if it’s actually called Paradise then maybe it’s just a tiki bar.

[v] Jannah, which is derived from an Arabic word for “garden,” shares the same linguistic lineage as the Hebrew tradition where “garden” became synonymous with the Garden of Eden and eventually “Paradise.”

__________________________________________________

|

Sohyong Lee (b. Chun Cheon, Korea) is a multidisciplinary artist who primarily works with sculpture, video, and installation. She received an MFA in Art-Integrated Media from the California Institute of the Arts and a BFA in Sculpture from the College of Art & Design, EWHA Womans University. Sohyong has shown her work at Cevera Yoon Gallery(CA), UTA Artist Space LA (CA), The Reef (CA), EWHA Art Gallery (Seoul, KR), Gallery Well (Seoul, KR), GyeomJae JeongSeon Art Museum (Seoul, KR), UM Gallery (Seoul, KR), Yihyung Art Center (Seoul, KR), Kosa Space Gallery (Seoul, KR). Her work has been featured in Voyage LA Local Stories. She works and lives in Los Angeles, California.

_

As a multidisciplinary artist working in sculpture and installation, I explore the visualization of subtle, momentary nature of the mundane, or in other words the daily instances that elude our habitual and linguistic perceptions. My work illuminates volatile ideas that hover at the edge of consciousness within the complexity of an ever-changing world, engaging in a contemplative examination of ungraspable senses we often overlook in daily experience.

By sustaining attention to the seemingly mundane things, each observation, however small they may be, becomes a catalyst for a deeper exploration. – An unexpected contrast, a trace of thoughts that reside in fleeting moments and how those nuances are transcribed through our mind. – Those inquiries are translated into a visual vocabulary through various techniques and modalities including molding, casting, crafting, integration of found objects, video, projection, and interactive coding. Through creating analogical relationships, I create intersections that initiate unfamiliar dialogue with the familiar, where fleeting moments find their visual voice in minimal, poetic forms that suggest rather than a declaration. Through this contemplative approach, I seek a pathway to revisit the fleeting nature of perception itself, reflecting on the significance of the profound impact of unnoticed facets of life, and guiding us toward an unexpected territory of insight, a renewed relationship with the ordinary.

|

Born in 1949 in Leninakan, Armenia, Rudik Ovsepyan became a member of the Artists’ Union of the USSR (CCCP) in 1982, eventually being banned for his refusal to paint in the propagandistic style of “social(ist) realism” (while continuing to produce and show abstract works). From 1966-1969, he attended Terlemesyan Fine Art College in Armenia. In 1974, graduated from the prestigious state State Academy of Theatre and Fine Arts in Yerevan. Facing the widespread destruction of the 1988 Spitak earthquake, as well the evolving political turmoil surrounding his abstract painting, Ovsepyan and his family moved (by boat) to Germany in 1990, where he became a member of the Fine Art Association of Germany (in 1994). There, several solo and group presentations of his work occurred in gallery, state, and museum exhibitions. In 2000, a major exhibition of Ovsepyan’s abstract works with oil and paper produced between 1996-1999 was presented by the German ministry of Education, Science, Research and Culture of Schleswig-Holstein (presented in Kiel). Later that year, Ovsepyan immigrated to the United States and began working on new bodies of work, including Labyrinth, Magaxat, and Zaun, while also beginning to produce mixed-media sculptures.

Ovsepyan’s works are included in public and private collections in Russia, Europe, Israel, Canada, and the United States, including: UNESCO, Geneva, Switzerland; Pushkin Museum, Moscow; Museum of Modern Art, Armenia, Yerevan; Museum of Modern Art, Georgia, Tblisi; Sparkasse Schleswig-Holstein, Germany; Sparkasse, Muenster, Germany; Provincial Versicherung; Bundesministerium der Verteidigung, Kiel, Germany.

|

Danica is an interdisciplinary artist. Their recent sculptural works investigate identity and autonomy through examining dissociation—a site where constructs of selfhood dissolve—and we are offered a chance to recompose. What survives in the space between presence and absence? They combine readymades with created pieces to reimagine modes of operation.

Danica’s recent work with performance has given them a critical outlet to recontextualize themself within their Basque heritage. Utilizing voice and movement as mediums of resistance against hegemonic pressures.

Danica is receiving their BFA at Otis College of Art and Design with an emphasis in Sculpture and New Genres. They are from Burlingame, California and are currently based in Los Angeles, California.

|

santoni kina is an interdisciplinary artist born and raised in Kenya, living and working in Los Angeles, CA. Their work records the body as a site for investigation, where themes around identity and intimacy can be explored. Producing through a range of mediums and methods, santoni works to understand their community, positionality and consequent experience.

They are currently pursuing their BFA at Otis College of Art and Design and attended Yale Norfolk School of Art 2024.

|

Keywan Tafteh, a Russian/Iranian/American artist, refuses to limit himself to a single medium. Using a combination of drawing, painting, collage, photography, video, computing, sculpture, and sound, Tafteh blurs the confines of genre to create sensory and emotional work.

Born in Austria and denied citizenship due to his parents’ refugee status, Tafteh immigrated to the United States as an infant. To this day a complicated cultural identity and questions of origin are foremost in his mind.

His creative process is informed by multiple painful and joyous themes: geographic and cultural displacement, the addiction of a loved one, otherness, technological innovation and the sheer joy of observation. Ancient Persian and Russian folk art resonate with his heritage and are of particular interest to Tafteh. This interest is complicated by the transformation of these formerly tolerant societies to institutionalized homophobia. His work explores this societal shift. In short, he creates art that serves as a coping mechanism while celebrating life.

Tafteh studied at the California College of the Arts, San Francisco, California, and at the ArtCenter College of Design, Pasadena, California. He is currently enrolled at the University of California San Diego, where he is pursuing a Bachelor of Arts degree in Studio Arts, with a minor in Interdisciplinary Computing and the Arts.

In addition to his studies, Tafteh taught introductory robotics workshops during the summer of 2019— both at Southwestern College, Chula Vista, California, and at San Diego State University, San Diego, California. During the pandemic, he taught a introductory JavaScript/HTML course at UC Riverside. These workshops were through Upward Bound, a program offering low-income high school students the chance to study at major universities.

|

Born and raised in Los Angeles, California, Tiago Da Cruz is a visual artist making work in and around the mediums of both Drawing and Photography. Tiago is working with making enlargements on gelatin silver paper that undergo iterative cycles of inversion. He is interested in working within the medium of photography through fading of images in the process of solar and lunar exposures on light sensitive paper.

He often uses expired and found materials, collapses time through prolonged exposures, records memory, and refuses use of “new material,” essential for his processes of queering and breaking down photographs. In 2022, Tiago received their BFA in Photography from California College of the Arts. He was selected as one of the exhibiting artists of the 2024 Forecast exhibition at SF Camerawork. Tiago currently is based in Los Angeles, California where he lives and works.

_

Through my process of fading images, I reflect on the instability and temporality of traditional photographic image making. I am concerned with expiration; expired material collapses time into a sheet of photo paper. I expose expired light sensitive gelatin silver paper for prolonged periods of time to the light from the sun and moon over the course of hours, days, and weeks. By embracing the natural decay and transformation of images over time, my work invites viewers to reconsider the temporal nature of all things, including artistic expression. Integrating fragments from my images into books and onto gelatin silver photographs, I incorporate physical pieces like test strips from my darkroom process.

My practice merges memory, abstraction, and time through distortions of analog photographic processes. My way of working with traditional processes is expressed in non-traditional notions of permanence in art-making by manipulating images through iterative exposures to natural light on expired materials. I question the stability of a photograph by tracking and exhibiting its transformation. I use my darkroom-printed photographs as paper negatives and positives, exposing them with a new sheet of expired light sensitive paper. This results in a monochromatic image softened by the dislocation of visual clarity. All of my photographic works are able to be used as paper negatives or positives and can be viewed as part of my process or included as finished works. As each iteration unfolds, traces of the original images dissolve into soft fading photographs, shifting to less recognizable forms.

_______________________________________________

____

Screening: santoni kina. ‘maybe now i won’t be so hungry (chewed clay)’ . 25lbs of Dark Horse LC 5, my mouth. performed november 30th 2024. video duration - 00:06:36.

Currently Exhibiting: (paradise) . January 25 – March 1, 2025. Sohyong Lee, Rudik Ovsepyan, Danica Ribi, santoni kina, Keywan Tafteh, Tiago Da Cruz. Group exhibition.

….

Friday, February 21, the gallery is screening a video by santoni kina along their participation in the current group exhibition (paradise).

The screening is set to begin at 8pm. Doors open at 7:30pm.

The video works with footage of santoni chewing-through a 25-pound bag of clay: Dark Horse LC 5.

….

Right Now

…with all the woosh of commerce in the air… with all the wants and gets of the art fairs going-on right now… this work remembers something necessary about the ways we circulate through works of art. Maybe it shows something needed that doesn’t immediately have anything to do with something being bought and sold, while having everything to do with consumption—eating, wanting, having…. An attempt at a cure (or a curse) that turns-back to seething states of desire and demand: consumption is back with a body. Back to the ground of taste: hunger. —What do I want? Why do I need to have it? What do I need to want?….

….

Geophagycs—or, a preliminary timeline of eating the earth in contemporary art

o. Out West: some performances that incorporate clay (since the 60s):

+ 1960s–1970s: Early Experiments with Clay in Performance

- Robert Rauschenberg – "Mud Muse" (1968–71)

- Ana Mendieta – "Silueta Series" (1973–78)

- Joseph Beuys – "Eurasia Siberian Symphony" (1966)

+ 1980s–1990s: Clay as a Metaphor for the Body

- Antoni Miralda – "Breadline" (1977–1990s)

- Anish Kapoor – "Shooting into the Corner" (2008–2009)

+ 2000s–Present: Contemporary Uses of Clay in Performance

- William Cobbing – "The Kiss" (2004–present)

- Adrian Villar Rojas – "The Most Beautiful of All Mothers" (2012)

- Clifford Owens – "Anthology" (2011–2012)

- Paweł Althamer – "Venetians" (2013)

[—80. February 2025. (v0p0.)]

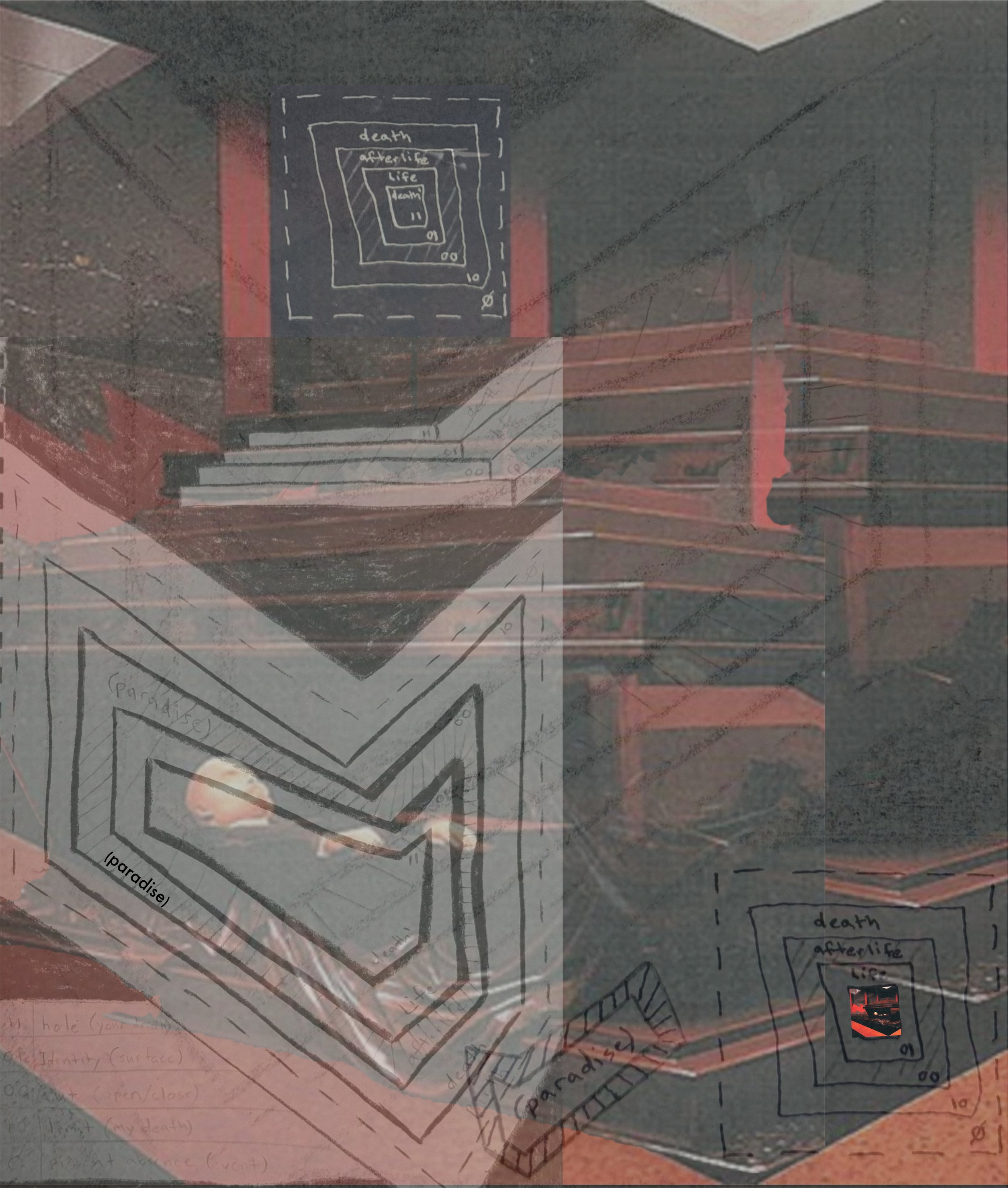

Exhibition Topology (Diagram)

Diagram of Lenin's Mausoleum. (Located in the Red Square, Moscow, Russia.)

....

(paradise) . Sohyong Lee, Rudik Ovsepyan, Danica Ribi, santoni kina, Keywan Tafteh, Tiago Da Cruz. January 25 – March 1, 2025. Group exhibition.

Image: Installation View\ Night (0). Positioned at gallery-front (right). Oriented forward, facing gallery-penultimate. [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Image: Installation View\ Night (1). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Image: Installation View\ Night (2). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Image: Installation View\ Night (3). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Image: Installation View\ Night (4). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Image: Installation View\ Night (5). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Image: Installation View\ Night (6). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. 2022. Bookbinding gauze, dictionary, steel, water, video projection loop. [Installation View\ Night.]

Image: Installation View\ Night (7). Positioned at gallery-penultimate. Oriented toward gallery-front with view of left-hand wall. [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Danica Ribi. Vestige . 2024. Paraffin wax, cellophane, duct tape, paper, bakers racks, pipe clamps, fragment of wall, rags, Virgin Mary. Dimensions variable. [Installation View\ Night.]

Image: Installation View\ Night (7). Positioned at gallery-penultimate. Oriented toward gallery-front with view of right-hand wall; with a partial view of front window. [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Population View\ Night. Opening Reception: Saturday, January 25, 6pm - 9pm.

Sohyong Lee. Longing Shadows . 2023. Wooden frame, still image, tiny video player, video loop. 9 x 9 x 2 inches. [Installation View\ Day.]

Sohyong Lee. Longing Shadows . 2023.

Sohyong Lee. Longing Shadows .

Sohyong Lee. Longing Shadows . [Detail.]

Sohyong Lee. Longing Shadows . 2023. [Side-view; small video visible.]

Keywan Tafteh. Nbaby . 2024. Acrylic paint, charcoal drawing on newsprint, found photograph, notes, newspaper, tape, collage on wood board. 26.5 x 22 inches.

Keywan Tafteh. Nbaby . 2024. [Detail.]

Keywan Tafteh. Nbaby . [Detail.]

Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . 2024-2025. Mixed Media on Cardboard. 12 x 9 inches (each).

Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . 2024-2025. [L.]

Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . 2024-2025. [M.]

Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . 2024-2025. [R.]

Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . [L: Detail.]

Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . [M: Detail.]

Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . [R: Detail.]

Tiago Da Cruz. cellulose . 2024. Gelatin silver prints. 9.4 x 35.4. inches.

Tiago Da Cruz. cellulose . 2024. [L: Detail.]

Tiago Da Cruz. cellulose . [M: Detail.]

Tiago Da Cruz. cellulose . [R: Detail.]

Sohyong Lee. Place, temporary . 2024. Wood, metal rods, latex, cement, fishing wire. ≈ 17 x 17 x 77 inches. [Installation View\ Day.]

Sohyong Lee. Place, temporary . 2024. [Partial: top.]

Sohyong Lee. Place, temporary .

Sohyong Lee. Place, temporary . [Detail.]

Sohyong Lee. Place, temporary . [Detail.]

Sohyong Lee. Place, temporary . [Partial: lower.]

Sohyong Lee. Place, temporary . [Detail.]

Sohyong Lee. Place, temporary .

santoni kina. U looking? . 2024. Tracing paper, image, text, a fan, screws. 11 x 8.5 prints (dimensions variable). [Installation View\ Day.]

santoni kina. U looking? . 2024.

santoni kina. U looking? . 2024.

santoni kina. U looking? . 2024.

Tiago Da Cruz. brush . 2025. Gelatin silver print. 16 x 20 inches.

Tiago Da Cruz. brush . 2025. [Closer.]

Tiago Da Cruz. brush . [Detail.]

Tiago Da Cruz. releasing . 2024. Gelatin silver print. 16 x 20 inches.

Tiago Da Cruz. releasing . 2024. [Closer.]

Tiago Da Cruz. [Installation View\ Morning.]

Danica Ribi. Vestige . 2024. Paraffin wax, cellophane, duct tape, paper, bakers racks, pipe clamps, fragment of wall, rags, Virgin Mary. Dimensions variable. [Installation View\ Day.]

Danica Ribi. Vestige . [Partial: detached.]

Danica Ribi. Vestige . [Partial: left.]

Danica Ribi. Vestige . [Partial: right.]

Danica Ribi. Vestige . 2024. [Partial: top.]

Danica Ribi. Vestige . [Detail.]

Keywan Tafteh. Duty Call . 2024. Spray paint, marker, porno clippings, matte board, collage on particle board (shelf). 22 x 17 inches.

Keywan Tafteh. Duty Call . 2024. [Detail.]

Keywan Tafteh. Duty Call . [Detail.]

Rudik Ovsepyan. Untitled . 2023-2025. Mixed Media on Cardboard. 22 x 19 inches.

Rudik Ovsepyan. Untitled . 2023-2025. [Detail.]

Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. 2022. Bookbinding gauze, dictionary, steel, water, video projection loop. [Installation View\ Night. (Photography: Sohyong Lee.)]

Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. 2022. [Installation View\ Night. (Photography: Sohyong Lee.)]

Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. [Installation View\ Night. Partial. (Photography: Sohyong Lee.)]

Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. [Installation View\ Night. Partial. (Photography: Sohyong Lee.)]

Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. [Installation View\ Night. Detail. (Photography: Sohyong Lee.)]

Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. [Installation View\ Night. Partial. (Photography: Sohyong Lee.)]

Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. [Installation View\ Night. Partial. (Photography: Sohyong Lee.)]

Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. [Installation View\ Night. Oblique. (Photography: Sohyong Lee.)]

Mailslot View/ Morning. Positioned at gallery-threshold. Oriented toward gallery-interior, peering through open mailslot. Visible: santoni kina. U looking? . 2024. Tracing paper, image, text, a fan, screws. 11 x 8.5 prints (dimensions variable).

![Image: Installation View\ Night (0). Positioned at gallery-front (right). Oriented forward, facing gallery-penultimate. [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/5936ffde-409a-4251-9a00-0ede4b5498a1/Install+7.jpg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (1). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/3e56001d-ff66-456d-9338-f60d0c5675f9/Install+6+B.jpg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (2). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/df106598-1d1a-4c85-93c1-cbaedb41e77f/Install+5+B.jpg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (3). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/7c223494-1dac-4e1c-b140-2e61fcd4dffe/Install+4+D.jpg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (4). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/83ddb838-70af-4b89-b250-2c98c71f1184/Install+8.jpg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (5). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/65692903-255d-4c2d-a814-0c5035b4f425/Install+9+B.jpg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (6). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/573257e0-010d-4b00-97b7-0b657c6c1b56/Install+1+B.jpg)

![Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. 2022. Bookbinding gauze, dictionary, steel, water, video projection loop. [Installation View\ Night.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/b769f0d6-ee72-45cb-a17a-15fd1bc0cd80/Install+11.jpg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (7). Positioned at gallery-penultimate. Oriented toward gallery-front with view of left-hand wall. [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/8ee79f74-c076-464f-8411-a73961426b7c/Install+3.jpg)

![Danica Ribi. Vestige . 2024. Paraffin wax, cellophane, duct tape, paper, bakers racks, pipe clamps, fragment of wall, rags, Virgin Mary. Dimensions variable. [Installation View\ Night.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/64e6dd50-11b4-488e-bad9-f349e9bae062/Install+10+B.jpg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (7). Positioned at gallery-penultimate. Oriented toward gallery-front with view of right-hand wall; with a partial view of front window. [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/9a1eccea-45d1-4e8b-8eff-1a1fd86b982b/Install+2+B.jpg)

![Sohyong Lee. Longing Shadows . 2023. Wooden frame, still image, tiny video player, video loop. 9 x 9 x 2 inches. [Installation View\ Day.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/31952fdd-386a-4e2e-a056-e5f1c3dbb51a/IMG_6295.jpg)

![Sohyong Lee. Longing Shadows . [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/ab744660-17a0-4849-9a3d-2fc1d1997a29/IMG_6302.jpeg)

![Sohyong Lee. Longing Shadows . 2023. [Side-view; small video visible.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/33295850-cf9d-4852-89ce-0e9355aa7df7/IMG_6304.jpg)

![Keywan Tafteh. Nbaby . 2024. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/413e7f06-a34e-4413-a189-692d06c286cd/IMG_6287.jpg)

![Keywan Tafteh. Nbaby . [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/8a57c0a3-970d-4164-a372-38057853b32e/IMG_6288.jpg)

![Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . 2024-2025. [L.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/fe701d38-fcca-4196-b0cb-23a854f07301/IMG_6243.jpg)

![Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . 2024-2025. [M.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/771ffb72-8bf6-45fc-932e-27e3c2dbbe29/IMG_6244.jpg)

![Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . 2024-2025. [R.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/f553bf12-30a3-4be1-bd8d-ddafa081ead4/IMG_6245.jpg)

![Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . [L: Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/efa3dc30-3433-4ea1-8f8c-ccd87cc1e06c/IMG_6246.jpeg)

![Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . [M: Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/de80697e-39bf-4367-bc54-7dfa54d93d3e/IMG_6247.jpeg)

![Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . [R: Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/85000d80-0665-454c-9d76-ed1b281fac23/IMG_6248.jpeg)

![Tiago Da Cruz. cellulose . 2024. [L: Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/afe3f4e8-3633-4784-a213-1d2ed56e87d8/IMG_6236.jpg)

![Tiago Da Cruz. cellulose . [M: Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/6639b8ac-a00c-4feb-993c-b9797a159d6f/IMG_6237.jpg)

![Tiago Da Cruz. cellulose . [R: Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/101e3e5d-71a4-465a-998e-fc8742c411b9/IMG_6238.jpg)

![Sohyong Lee. Place, temporary . 2024. Wood, metal rods, latex, cement, fishing wire. ≈ 17 x 17 x 77 inches. [Installation View\ Day.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/3849057d-5a4d-4256-973a-717733f07ffe/IMG_6868.jpg)

![Sohyong Lee. Place, temporary . 2024. [Partial: top.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/84ccc090-62f2-46b0-ba7a-e4b85af773be/IMG_6220.jpeg)

![Sohyong Lee. Place, temporary . [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/aaea354d-2503-46b9-8253-f7602a67151e/IMG_6891.jpg)

![Sohyong Lee. Place, temporary . [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/18db8685-2c2d-4897-92f6-573de9798670/IMG_6222.jpeg)

![Sohyong Lee. Place, temporary . [Partial: lower.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/40b9754b-bafb-457a-9561-8252f957699d/IMG_6226.jpeg)

![Sohyong Lee. Place, temporary . [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/c013e72d-a243-472f-a75c-e7ff66fb66c0/IMG_6228.jpeg)

![santoni kina. U looking? . 2024. Tracing paper, image, text, a fan, screws. 11 x 8.5 prints (dimensions variable). [Installation View\ Day.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/13071f5d-b529-439b-98f6-95d4770006c6/IMG_6347.jpg)

![Tiago Da Cruz. brush . 2025. [Closer.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/7bb90058-4d18-437b-8b7e-9c292109e280/IMG_6206.jpeg)

![Tiago Da Cruz. brush . [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/62a6aac3-8604-44a1-9abb-a80df7949242/IMG_6207.jpeg)

![Tiago Da Cruz. releasing . 2024. [Closer.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/ccda888a-8390-4c1b-aeb5-a7628fb35aea/IMG_6209.jpeg)

![Tiago Da Cruz. [Installation View\ Morning.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/f6213cdf-74c0-427f-a0ef-b576bff25913/IMG_6203.jpg)

![Danica Ribi. Vestige . 2024. Paraffin wax, cellophane, duct tape, paper, bakers racks, pipe clamps, fragment of wall, rags, Virgin Mary. Dimensions variable. [Installation View\ Day.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/35382ba1-334b-4734-8595-051a766a0ac4/IMG_6260.jpg)

![Danica Ribi. Vestige . [Partial: detached.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/09324b29-035a-41da-b45a-478995cdd1f1/IMG_6267.jpeg)

![Danica Ribi. Vestige . [Partial: left.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/236ac886-c716-483d-9096-662f9a90441d/IMG_6277.jpg)

![Danica Ribi. Vestige . [Partial: right.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/f77e82ec-49cf-49ef-882e-1e64a310affa/IMG_6278.jpg)

![Danica Ribi. Vestige . 2024. [Partial: top.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/cba87d06-5db6-47e3-a102-5243daf9b187/IMG_6864.jpg)

![Danica Ribi. Vestige . [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/572cbb99-e54a-4266-a603-4e624d8887cf/IMG_6281.jpg)

![Keywan Tafteh. Duty Call . 2024. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/92741b6e-63b0-4b83-aa17-833d37c7ccdc/IMG_6292.jpg)

![Keywan Tafteh. Duty Call . [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/f848dfb5-449e-467a-851b-ea617e9441f9/IMG_6294.jpg)

![Rudik Ovsepyan. Untitled . 2023-2025. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/2fef1951-86a5-49fb-a6d3-5b5e3bf3bbbb/IMG_6316.jpeg)

![Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. 2022. Bookbinding gauze, dictionary, steel, water, video projection loop. [Installation View\ Night. (Photography: Sohyong Lee.)]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/ad4d6991-8696-4c0d-9ce4-2818514e930d/DeepShallow_high_2.jpg)

![Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. 2022. [Installation View\ Night. (Photography: Sohyong Lee.)]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/fd068b15-d812-45cd-81f2-fab95e667bf7/DeepShallow_high_1.jpg)

![Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. [Installation View\ Night. Partial. (Photography: Sohyong Lee.)]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/2e4882a3-eebd-443b-a1c3-fb49ac00818a/DeepShallow_high_3.jpg)

![Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. [Installation View\ Night. Partial. (Photography: Sohyong Lee.)]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/cf3e07b5-54d4-451f-acdd-84944f45d5b1/DeepShallow_high_4.jpg)

![Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. [Installation View\ Night. Detail. (Photography: Sohyong Lee.)]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/ad0ff286-64b5-45bd-b2b1-b14c0ec2514e/DeepShallow_high_5.jpg)

![Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. [Installation View\ Night. Partial. (Photography: Sohyong Lee.)]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/9f16225f-5dec-435e-a2a3-bc0a3fe8d5de/DeepShallow_high_7.jpg)

![Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. [Installation View\ Night. Partial. (Photography: Sohyong Lee.)]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/9b2854c7-1633-45cb-a8d5-039d89042d90/DeepShallow_high_8.jpg)

![Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. [Installation View\ Night. Oblique. (Photography: Sohyong Lee.)]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/efd05644-f214-4d7e-82cd-711df210e617/DeepShallow_high_9.jpg)