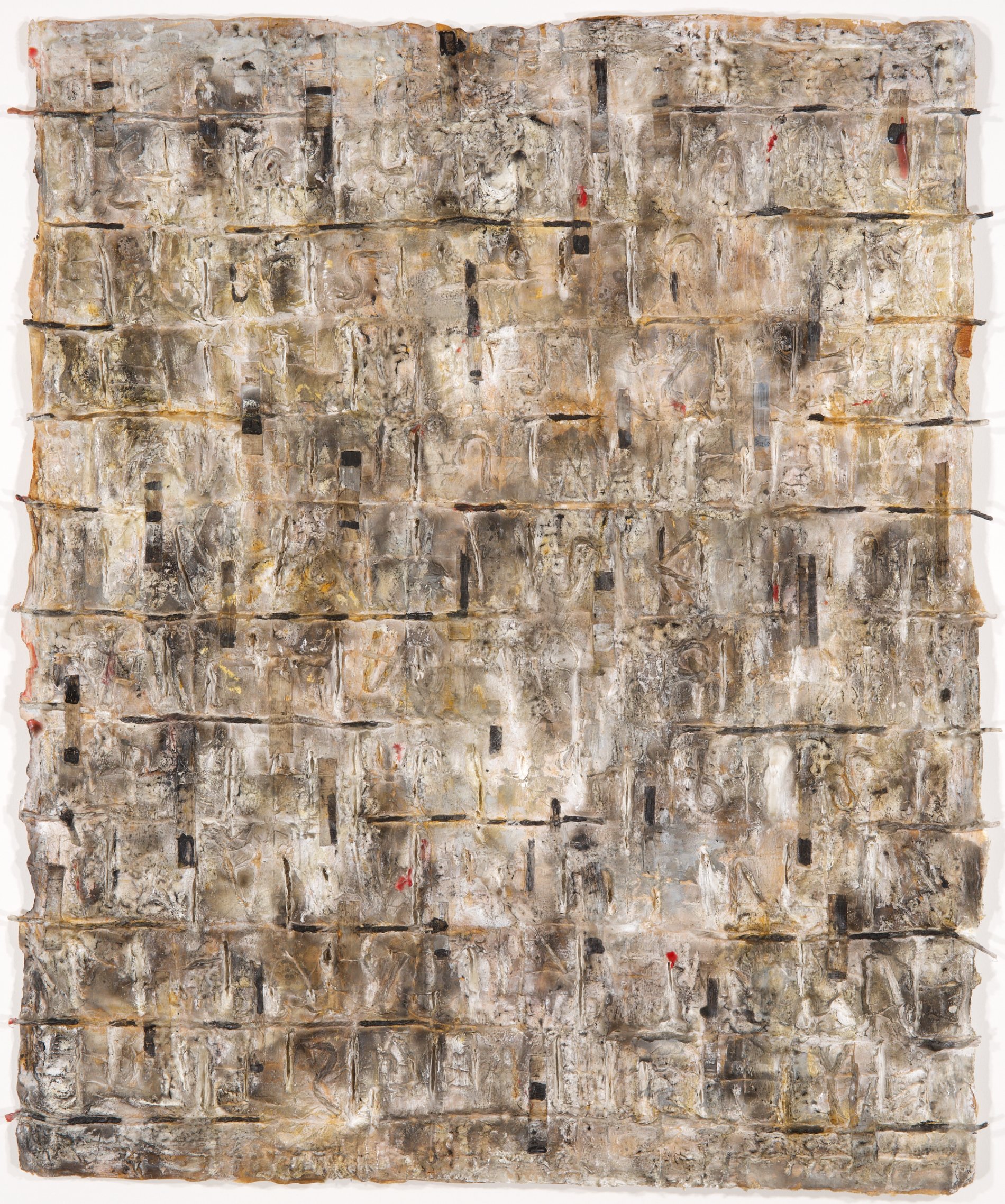

Untitled (Labyrinth Series). 2009. Mixed Media on Cardboard. 17 × 15 1/2 × 1/10 inches.

Rudik Ovsepyan (b. 1949: Leninakan, Armenia)

Represented by Reisig and Taylor Contemporary.

Dealer Contact: Emily Reisig.

.

Exhibitions Images and Recordings: View.

||||

Recent Exhibition:

January 25 – March 1, 2025. Winter. Los Angeles (4478).

Sohyong Lee, Rudik Ovsepyan, Danica Ribi, santoni kina, Keywan Tafteh, Tiago Da Cruz

+ Reference: Checklist.

+ Release: File.

+ Press: This Week’s Must-See Art (Curate LA: February 20-26, 2025).

+ Exhibition Documentation : View.

|

Mixed-Media Artist currently living in Los Angeles.

Former (Banned) Member of the Artists’ Union of the USSR (CCCP).

Member of the Artists’ Union of the Armenia.

Member of the Fine Art Association of Germany (Bundesverband Bildender Künstler, Landesverband Schleswig-Holstein) (BBK).

….

Bio

Born in 1949 in Leninakan, Armenia, Rudik Ovsepyan became a member of the Artists’ Union of the USSR (CCCP) in 1982, eventually being banned for his refusal to paint in the propagandistic style of “social(ist) realism” (while continuing to produce and show abstract works). From 1966-1969, he attended Terlemesyan Fine Art College in Armenia. In 1974, graduated from the prestigious state State Academy of Theatre and Fine Arts in Yerevan. Facing the widespread destruction of the 1988 Spitak earthquake, as well the evolving political turmoil surrounding his abstract painting, Ovsepyan and his family moved (by boat) to Germany in 1990, where he became a member of the Fine Art Association of Germany (in 1994). There, several solo and group presentations of his work occurred in gallery, state, and museum exhibitions. In 2000, a major exhibition of Ovsepyan’s abstract works with oil and paper produced between 1996-1999 was presented by the German ministry of Education, Science, Research and Culture of Schleswig-Holstein (presented in Kiel). Later that year, Ovsepyan immigrated to the United States and began working on new bodies of work, including Labyrinth, Magaxat, and Zaun, while also beginning to produce mixed-media sculptures.

Ovsepyan’s works are included in public and private collections in Russia, Europe, Israel, Canada, and the United States, including: UNESCO, Geneva, Switzerland; Pushkin Museum, Moscow; Museum of Modern Art, Armenia, Yerevan; Museum of Modern Art, Georgia, Tblisi; Sparkasse Schleswig-Holstein, Germany; Sparkasse, Muenster, Germany; Provincial Versicherung; Bundesministerium der Verteidigung, Kiel, Germany.

____

Exhibitions with the Gallery:

- January 25 – March 1, 2025. Winter. Los Angeles (4478).

Sohyong Lee, Rudik Ovsepyan, Danica Ribi, santoni kina, Keywan Tafteh, Tiago Da Cruz

+ Reference: Checklist.

+ Release: File.

+ Press: This Week’s Must-See Art (Curate LA: February 20-26, 2025).

+ Exhibition Documentation : View.

- April 25 - April 28, 2024. Political-Economy Project.

San Francisco Art Fair

Xiao He, Rudik Ovsepyan, objet A.D, Chris Reisig and Leeza Taylor

+ Reference: Checklist.

- March 2 - April 6, 2024. Group Exhibition.

Claudia Rega, Frantz Jean-baptiste, Grant Falardeau, Xiao He, Daniela Soberman, Rudik Ovsepyan, Sinclair Vicisitud.

+ Reference: Checklist.

+ Release: File.

+ Press: This Week’s Must-See Art (Curate LA: February 29-March 6, 2024); LA Art Openings & Spotlight (ArtRabbit: February 28, 2024).

- Winter – Spring, 2024. Group Exhibition.

Rudik Ovsepyan, Suwichada Busamrong-Press, Erica Everage, Sinclair Vicisitud, objet A.D, and Chris Reisig & Leeza Taylor.

+ Release: File

+ Reference: Checklist

+ Release: File.

-- September 30 - October 4. Benefit Salon.

Emma Gray, Daniela Soberman, Ari Salka, Erica Everage, Kento Saisho, Keywan Tafteh, Sinclair Vicisitud, Suwichada Busamrong-Press, Saun Santipreecha, Rudik Ovsepyan, objet A.D, Chris Reisig & Leeza Taylor.

+ Reference: Checklist.

+ Recordings: Exhibition Videos.

+ Press: This Week’s Must-See Art (Curate LA: September 28-August 4, 2023).

- August 26 - September 23, 2023. Historical survey.

Magaxat | Survey (1976 - Present)

+ Reference: Checklist.

+ Release: Page.

+ Publication: Limited Edition Print Catalogue; Digital Catalogue (Part 1, Part 2).

+ Recordings: Exhibition Videos.

+ Press: Review by Joseph A. Hazani (A Dilettante: September 23, 2023); Film by EMSARTS (August 27, 2023); This Week’s Must-See Art (Curate LA: August 24-August 30, 2023).

+ Events: Performance (Release); Curator Walkthrough (Release).

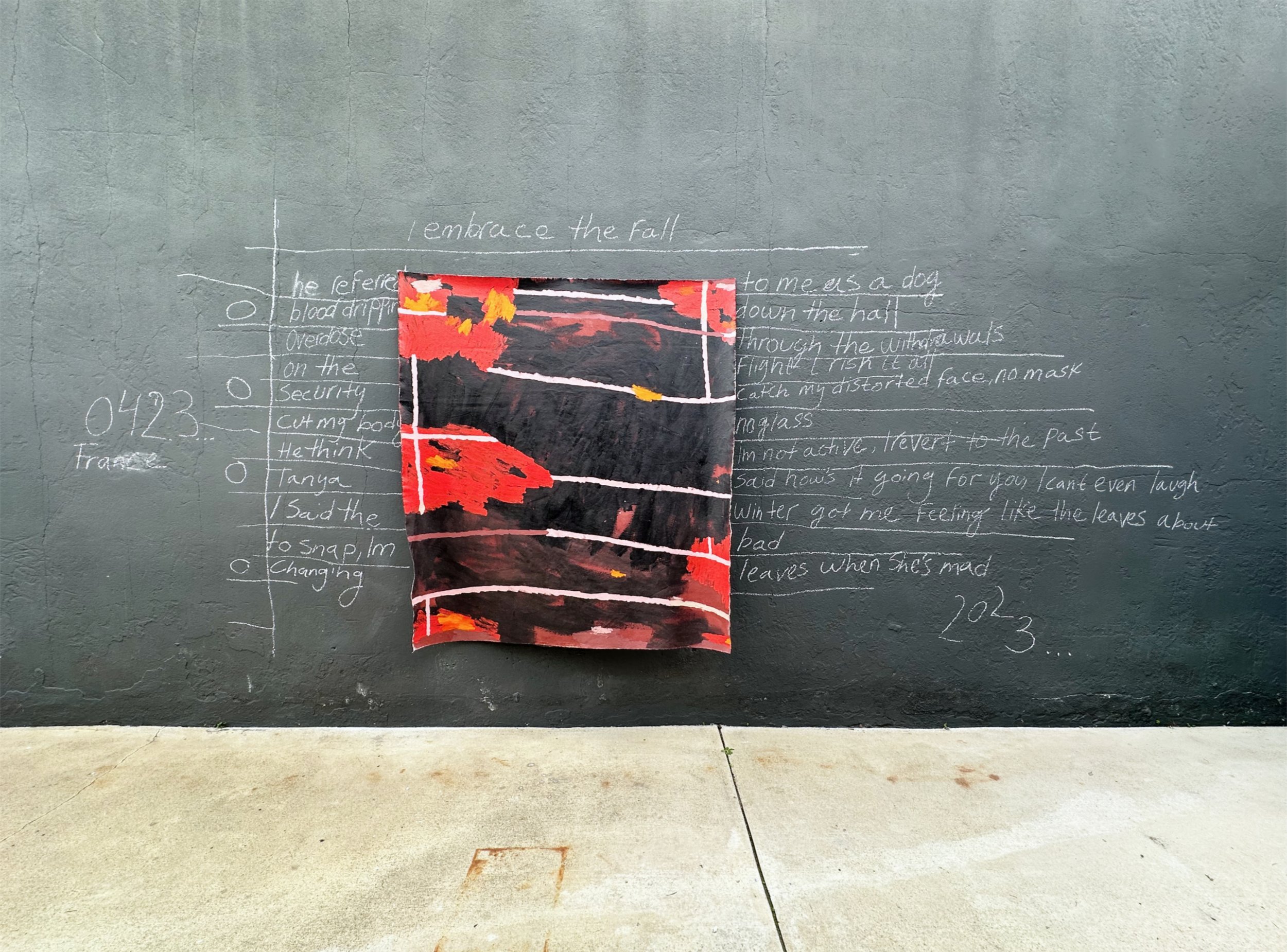

- April 20 - April 23, 2023. San Francisco Art Market. Political-Economy Project.

Sinclair Vicisitud, Rudik Ovsepyan, objet A.D, Chris Reisig & Leeza Taylor.

+ Document: Catalogue

____

Inquire for Information, Image Details, or Status of Exhibited Works:

....

(paradise) . Sohyong Lee, Rudik Ovsepyan, Danica Ribi, santoni kina, Keywan Tafteh, Tiago Da Cruz. January 25 – March 1, 2025. Group exhibition. | Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . 2024-2025. Mixed Media on Cardboard. 12 x 9 inches (each).

Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . 2024-2025. [L.]

Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . 2024-2025. [M.]

Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . 2024-2025. [R.]

Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . [L: Detail.]

Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . [M: Detail.]

Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . [R: Detail.]

Rudik Ovsepyan. Untitled . 2023-2025. Mixed Media on Cardboard. 22 x 19 inches.

Rudik Ovsepyan. Untitled . 2023-2025. [Detail.]

(paradise) . Sohyong Lee, Rudik Ovsepyan, Danica Ribi, santoni kina, Keywan Tafteh, Tiago Da Cruz. January 25 – March 1, 2025. Group exhibition.

Image: Installation View\ Night (0). Positioned at gallery-front (right). Oriented forward, facing gallery-penultimate. [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Image: Installation View\ Night (1). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Image: Installation View\ Night (2). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Image: Installation View\ Night (3). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Image: Installation View\ Night (4). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Image: Installation View\ Night (5). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Image: Installation View\ Night (6). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. 2022. Bookbinding gauze, dictionary, steel, water, video projection loop. [Installation View\ Night.]

Image: Installation View\ Night (7). Positioned at gallery-penultimate. Oriented toward gallery-front with view of left-hand wall. [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Danica Ribi. Vestige . 2024. Paraffin wax, cellophane, duct tape, paper, bakers racks, pipe clamps, fragment of wall, rags, Virgin Mary. Dimensions variable. [Installation View\ Night.]

Image: Installation View\ Night (7). Positioned at gallery-penultimate. Oriented toward gallery-front with view of right-hand wall; with a partial view of front window. [Photography: Chris Reisig.]

Other Days. Claudia Rega, Frantz Jean-baptiste, Grant Falardeau, Xiao He, Daniela Soberman, Rudik Ovsepyan, Sinclair Vicisitud. March 2 – April 6, 2024. Group Exhibition. | Installation View\Day (1).

{Upper} Rudik Ovsepyan. Sunday, 1976. Tempera and Ink on Paper. 17 x 12 inches unframed (25 x 21 inches framed). {Lower} Grant Falardeau. Heart Face. 2024. Ceramic, pastel. 12 x 12 x 12 inches.

Rudik Ovsepyan. Sunday, 1976. Tempera and Ink on Paper. 17 x 12 inches unframed (25 x 21 inches framed).

Rudik Ovsepyan. Sunday, 1976. Tempera and Ink on Paper. 17 x 12 inches unframed (25 x 21 inches framed).

Rudik Ovsepyan. Sunday, 1976. Tempera and Ink on Paper. 17 x 12 inches unframed (25 x 21 inches framed). [Detail.]

Installation View\Day (4)

Rudik Ovsepyan. From Home (Memory), 2018. Mixed media on cardboard on plywood. 43 x 35 inches.

Rudik Ovsepyan. From Home (Memory), 2018. Mixed media on cardboard on plywood. 43 x 35 inches.

Rudik Ovsepyan. From Home (Memory), 2018. Mixed media on cardboard on plywood. 43 x 35 inches. [Detail.]

Untitled. 1976-1977. Tempera and Ink on Paper 17 x 12 inches (unframed). [A portrait of the artist's wife while she is pregnant.]

Untitled. 1976-1977. Tempera and Ink on Paper 17 x 12 inches (unframed). [A portrait of the artist's wife while she is pregnant.]

Untitled. 1991. Tempera, Charcoal, and Pastel on Paper. 16.5 x 12 inches (unframed).

Untitled. 1991. Tempera, Charcoal, and Pastel on Paper. 16.5 x 12 inches (unframed).

{Left} Untitled. 1976-1977. Tempera and Ink on Paper. 26.5 x 19.5 inches (unframed). {Right} Untitled. 1976. Tempera and Ink on Paper. 17 x 12 inches (unframed).

Untitled. 1976-1977. Tempera and Ink on Paper. 26.5 x 19.5 inches (unframed). [A study of the artist's studio in Armenia.]

Untitled. 1976. Tempera and Ink on Paper. 17 x 12 inches (unframed). [A portrait of the artist with his family.]

Vinter Jajur. 1977. Tempera on Paper. 16.5 x 17.5 inches.

Winter Mountain. 1977. Tempera on Paper 18 x 21 inches. {Available but not exhibited.}

Ancient City (Green). 2023. Zaun Series. Acrylic, Cement, Latex, Thread and Paper on Cardboard. 39.5 x 33 inches.

Ancient City (White). 2023. Zaun Series. Acrylic, Cement, Latex, Thread, Found Objects, and Paper on Cardboard. 41 x 35.5 inches.

Ancient City (Red), 2023. Zaun Series. Acrylic, Cement, Latex, Thread, Found Objects, and Paper on Cardboard. 41 x 35.5 inches.

The Red series.

Three paintings from the Red series.

Still Life. 1992. Red Series. Oil on Canvas. 38 x 30 inches.

10 Century Poet (Gregory of Narek). 1989. Red Series. Oil on Canvas. 39.38 x 29.38 inches.

Untitled. 1991. Red Series. Oil on Canvas. 31.63 x 27.63 inches.

Sacrifce. 1992. Red Series. Oil on Canvas. 45 x 29 inches.

Labirint. 2002. Mixed Media (Oil, Cardbaord, Wax, Newspaper) on Canvas. 35.5 x 47.5 inches.

Untitled. 2023. Mixed Media. 8 x 12 x 12 inches.

Untitled. 2023. Mixed Media. 8 x 12 x 12 inches.

Untitled. 2023. Mixed Media. 8 x 12 x 12 inches.

Untitled. 2005-2006. Magaxat Series. Mixed Media (Tempera, Wax, Pastel, Thread) on Cardboard. 17.5 x 14 inches.

Untitled, 2005-2006. Magaxat Series. Mixed Media (Tempera, Wax, Thread) on Cardboard. 17 x 13.5 inches.

Zaun. 2010. Mixed Media on Cardboard. 11.5 x 10.5 inches.

Zaun. 2010. Mixed Media on Cardboard. 11.5 x 10.5 inches.

Untitled. 2011. Labyrinth Series. Mixed Media on Cardboard. 14 x 12.5 inches.

Rudik Ovsepyan. Untitled. 2004. Labyrinth Series. Mixed-Media on Cardboard. 17 x 15.5 inches. |Private Collection: San Francisco.|

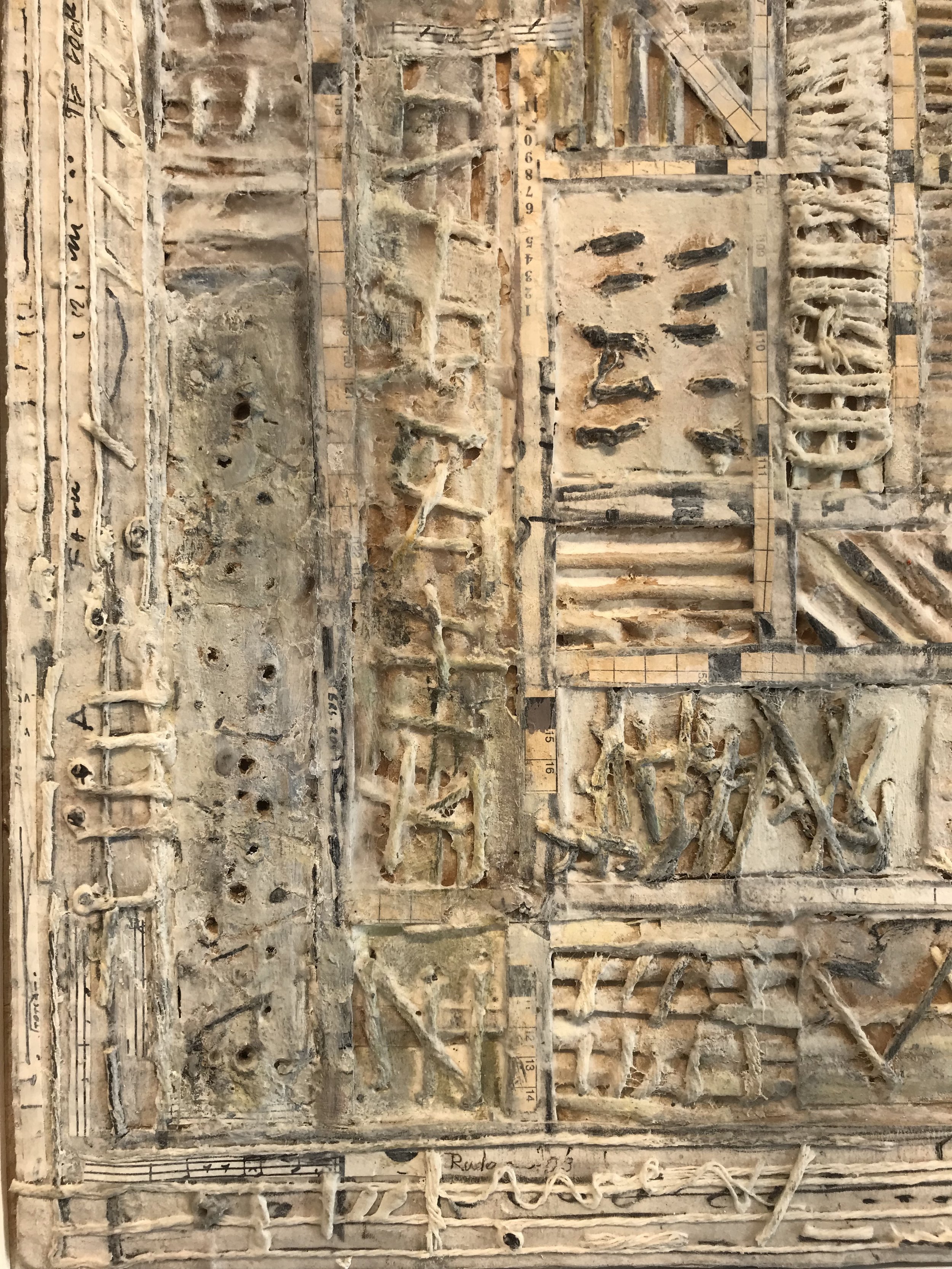

Untitled. 2011. Labyrinth Series. Mixed Media on Cardboard. 14 x 12.5 inches. (Detail.)

Untitled. 2009. Labyrinth Series. Mixed Media on Cardboard. 17 x 15.5 inches.

The Every Sense Of.... 2003. Mixed Media (Tempera, Wax, Thread) on Cardboard 18 x 17 inches.

The Every Sense Of.... 2003. Mixed Media (Tempera, Wax, Thread) on Cardboard 18 x 17 inches. (Detail.)

Untitled. 2008. Labyrinth Series. Mixed Media on Cardboard. 17 x 14 inches.

Three works from the Labyrinth Series.

Stilleben, 1998-1999. Mixed Media and Tempera on Paper (Print). 18.5 x 12 inches with Border (unframed). 1/1 Enkarel Print.

Stilleben. 1998-1999. Mixed Media and Tempera on Paper (Print). 21 x 15.25 inches with Border (unframed). 1/1 Enkarel Print.

Enkarel Mischtecknik. 1998-1999. Mixed Media and Tempera on Paper (Print). 18.5 x 12 inches with Border. 1/1 Enkarel Print with Mixed Technique.

Rudik Ovsepyan. Borderline. 2009. Mixed-Media on Linen. 36 x 36 inches.

Historiography

Born in 1949 in Leninakan, Armenia, Rudik Ovsepyan attended Terlemesyan Fine Art College in Armenia from 1966-1969. In 1974, graduated from the prestigious state State Academy of Theatre and Fine Arts in Yerevan. Ovsepyan is a former member of the Artists’ Union of the USSR (CCCP), having been banned for his eventual refusal to paint in the propagandistic style of “socialist realism” (while continuing to produce and show abstract works). Ovsepyan’s most prominent propaganda painting was a monumental-scale portrait of Leonid Brezhnev. It was this painting that helped formalize his position as a member of the Artists’ Union of the USSR (CCCP) in 1982. It was also this painting that helped him realize that he did not want this membership. Unwilling to corrupt or falsely politicize his personal artistic process, he continuously developed a practice of abstract painting while also working as a professional Soviet artist, making posters and creating commissioned works as financial and political means of survival. A double life: one as a painter, one as a Soviet painter. (A double, but not necessarily split, practice.) But he did not hide his work. After several exhibitions of both official and non-ordained (abstract) works in Armenia, Moscow, and the United States throughout the 1980s, his membership of the Artists’ Union of the USSR (CCCP) came to a sudden (but not unexpected) end during an exhibition in Moscow. When he arrived at the exhibition, his works were silently taken down in front of him and subsequently cut down the middle so they could not be shown. His artwork was banned and the KGB monitored his location and employment. Marked as a dissident, he was prevented from obtaining the documents that would allow him to immigrate to the United States (his ultimate plan).

But the political situation in the USSR was only one terrain of Ovsepyan’s struggle at this time. In 1988, the Spitak earthquake shook Armenia, razing buildings and killing at least 25,000 people. The destruction was especially widespread among the hastily-built Soviet-era apartment buildings in the northern industrial regions of Armenia. Ovsepyan lived with his family on the top-floor of one of these buildings. During the earthquake, the stairway collapsed and he and his wife were trapped on the 6th floor for days. Their children had been at school when the earthquake hit, so Ovsepyan and his wife were trapped without knowing the fate of their children. Further, the destruction of their home also meant that much of Ovspeyan’s artwork had been turned to debris. His home, his art, and his antique business shared the same wreckage. But his family was safe and remained intact. (Ironically, many blamed the poor-quality Soviet construction on the so-called “Era of Stagnation” brought about by Brezhnev’s rule—this is the same Soviet leader that was depicted in an honorary mural by Ovsepyan years earlier.)

Following the earthquake, Ovsepyan’s artistic production became rampant and compulsive as he worked-through the traumas of that experience. Enduring the same horrifying nightmare every time he fell asleep, he fell into his art in order to work with the material of his dreams and the source of his delirium. It was during this time that he began his Red series. Created in the immediate aftermath of 1988, these expressively-driven abstract figurative works display the space of his nightmares as ecstatic and harmonious, but slivered and collapsing fields of urban form seen through the red haze of hellish memory. These works combine the brightly-colored scenery of some his early landscapes and figurative works with his evolving tendencies toward geometric or puzzled abstraction. Paradoxically—or at least antagonistically—positioned themes of building, memory, and (dis)order become the fundamental elements of his abstract work produced from this series onward (‘88-). At this point, he is no longer a Soviet artist, but only an artist. Or, perhaps, an Armenian artist. The red paint for the Red works, made with a special blend of oils indigenous to Armenia along with the ancient vordan karmir—or, “worm’s red”—pigment sourced from the Armenian cochineal insect (a cochineal native to the Ararat Plain), infuses raw materials from his homeland directly into his work. This red cochineal pigment was widely used in medieval illuminated manuscripts in both Armenia and Turkey, and is metaphorically tied to Armenia’s industrialization throughout the Soviet period: this insect is now endangered due to the Soviet agriculturalization of the salt marshes required for the insects to reproduce. The use of this red pigment performs re-recording of an Armenian historical materiality before it is lost, colonized, or forgotten. Yet, despite its local ingredients, this recipe was crafted through his extensive study of the techniques of European masters, with a particular focus on Rembrandt. Locally sourced but globally, and historically, cultivated. This tension between place and material is a perennial relation throughout all of Ovsepyan’s work.

Ultimately, however, in order to wholly pursue the abstract artform that became his treatment and his cure, he would need to leave Armenia and the USSR. So he did. Ovsepyan and his family moved (by boat) to Germany in 1990, the same year the German Democratic Republic (or East Germany) was dissolved and the Berlin Wall dismantled. The event of the earthquake made it possible for Ovsepyan and his family to obtain a refugee status that allowed them to move. In 1992 they moved to Kiel, where they finally found a home officially beyond the reach of the USSR. Though he and his family struggled as refugees in Germany and found themselves at the social and political margins, he was, at the same time, able to gain citizenship through his art, eventually becoming a member of the Fine Art Association of Germany (Bundesverband Bildender Künstler (BBK), Landesverband Schleswig-Holstein). The exhibition of his Red series, “Roslinrot,” which was shown at Stadtkloster in Kiel, Germany in 1998, displayed a profound turning-point in his movement towards abstraction as a way of examining the unconscious, frenzied—but nonetheless ordered—pulsations of his practice as recording what he cannot otherwise process. An embodied friction between conscious and unconscious acts, carried-out by the work of art.

However, unlike the oil works of the Red series, the ensuing abstract works he produced while living in Germany (and later the United States) are almost exclusively mixed-media and collage. At first, much of the spark of his shift toward mixed-media seems to have come from necessity. Since he and his family were constantly moving under difficult circumstances, they were often unable to bring his work with them, and, therefore, Ovsepyan was forced to constantly recreate bodies of work with whatever he had (and with whatever would be light enough to travel with). One of the materials that is now a constant source in his work—cardboard—was a residue from this movement of displacement, the endless packing and unpacking of boxes, that came to be incorporated into his work. As both a literal and symbolic marker of his displacement, cardboard becomes the interstitial surface holding-together the patchwork of spaces, places, and times that make-up his unsettled homeland—as well as the primary material of his artwork. But there are traces of his movements and histories in other materials as well. For example, the newspaper clippings which are often collaged into many of the pieces from his current mode (1990-) always have both a local and historical significance. While living in Germany, Ovsepyan obsessively collected vintage newspapers from the Nazi-era and included these in his works. Sometimes the newspaper is left visible and entirely legible, sometimes it is slightly obscured; and sometimes it is entirely painted-over or encased by the materials—each variation showing a different moment of synthesis between memory/history (between what one does and what has already happened).

Re-finding and redefining his own narrative through the history of state violence in Germany, Ovsepyan found a deep connection between the Holocaust and the genocide of the Armenian people carried out by the Ottoman Empire’s Young Turk government during World War I (1914-18). This relation to the violent treatments of other marginalized groups in his new countries of residence became even more layered and complex upon his immigration to the United States. In his work Borderline (2009), created after immigrating to the United States from Germany, there are both newspaper clippings from Nazi-era German newspapers, as well as clippings from various U.S. publications having to do with civil rights, race relations, and the assassination of Martin Luther King Junior. With each phase of Ovsepyan’s life, he seamlessly folds one place into another, one history into another, through the act of his memory recorded on a surface. (And in his most recent body of work, he incorporates pills leftover from his wife’s work as a nurse as elements in his collaged pieces.) Moreover, his waxy “mummified” pieces—such as Zaun or ‘Fence’ (2010)—reach even further into the annals of the Armenian diaspora, recalling the ancient historical connections between Armenia and Egypt. With his works forming these tide pools of temporal and immigratory connections, his oeuvre always encounters itself as a simultaneous event of memory and history. This synchronic moment between personal life and historical context is a primary process of Ovsepyan’s work.

In both Ovsepyan’s early (figurative, landscape and still-life) work and his later abstract work, the concurrent aesthetic influence of Baroque, modern, and contemporary art, as well as medieval Armenian manuscripts, is present across series. These medieval manuscripts are inscribed with highly decorative Armenian script and sophisticatedly organized, puzzle-like structures formed through colorfully patterned borders. Similarly, his work is also evidently influenced by the colorful and ornately arranged imagery of traditional Armenian rugs. (Though, he often revisions such imagery with a minimal chromatic palette, as in the works from his Labyrinth series.) This habit of drawing inspiration from the deep historical contexts of Armenia remains a constant in his work, but these forms always evolve in translation—as residues, echoes, and memories—as Ovsepyan moves between places, materials, and techniques. Similarly, he incorporates ornamental and decorative elements of traditional Armenian crafts (such as rug-making) as ghostly ripples on the surfaces of his works, tracing their minimal force without repeating their exuberant form. This play between fine art and craftwork, high and low, continues to intensify, with some of his most recent works recreating Armenian ornamental designs using discarded bits of magazines, “painting” an elaborate design using only the colors already-found on the pieces of paper. In this case, a lowly material (magazine clippings) is transformed through craft (weaving/collage) in order to produce a fine (painterly) result. Refusing any class-organized, socially-valenced distinction of taste, all of Ovsepyan’s collage works (1994-) include this metamorphic process of ordinary, familiar materials realized in extraordinary, unfamiliar ways. (His early processes of sourcing raw materials for producing his own pigments, oils, and paints seems to preempt this emphasis on material as an interstitial visual language.)

Certainly, it is possible and perhaps effective to identify Ovsepyan’s work as Soviet “non-conformist” art; however, at the same time, it is important to recognize that the political orientation of his practice, like his place of dwelling, always remains elusive, slippery, and sliding—offering a fragmentary glimpse into a momentary, passing reality without overdetermining the statement or subject of any particular piece. Emerging at the historical end of the Soviet Union, his work increasingly reflects a blurry state of fragmentation and decay through his use of discarded objects, broken texts, and equivocal—but loaded—symbols: signs of a coming apocalypse. But this clairvoyance is always moving forward and backward at the same time. For example, when he alludes to medieval Armenian manuscripts in his Red series, this is only as an symbolic vehicle for a present trauma that may only be followed through this iconographic hall of mirrors where Ovsepyan attempts to re-find himself—and his destroyed homeland—through fractured memory. A future anterior. An apocalypse always already there at the very beginning. Looking at the Red works, each scene may seem to be a depiction of a celebration or sacrament, but this is only a symptom of the “all-knowing” perspective granted to viewer by the 2-dimensional field that equates visibility, showing, knowledge, and divinity through the puzzled constellation: undivided, with everything in view, everything appears in place. At a distance, the apparent completeness of the perspective suggests intention and ritual. But then the startled lines, split figures, and slivered architectures (arranged along deranged orthogonals) give way to a profound sense of displacement, of a population shaken, a place in ruins. In particular, with Untitled (1991) and Gregory of Narek (1989), the manuscriptive—omniscient, paneled (two-dimensional)—views of destroyed façades are presented as divine, but now fallen, perspectives, revealing collapsed buildings and razed rooms with their exterior walls shorn away. A simultaneous act of memory and history: a record.

While Ovsepyan is nearly an outsider to his own context, he was, to some degree, inspired by well-known Armenian predecessors like Minas Avetisyan, Martiros Saryan, and Arshile Gorky; and, it is certainly possible to see their influences in his early abstract landscapes and studies. In fact, Avetisyan was from the same village as Ovsepyan, Jajur, and painted many landscape sceneries of this place. Ovsepyan also painted many landscape sceneries of Jajur, and was, eventually, similarly pulled towards expression and abstraction through this mode of painting. However, despite this connection, his paintings remain highly idiosyncratic. Even these early works are readily distinguished from Avetisyan’s through Ovsepyan’s obsession with line and texture, and ultimately structure and de/construction, more so than color and representative nature (as is found in Avetisyan’s paintings). In terms of preceding (Soviet) movements that cast a shadow on his work, it seems his use of nonrational lettering and scription in his work continues features of the Zaum movement. And the geometrization of spaces, objects, and figures coinciding with lettering and symbols recalls essential features of Russian (Cubo-)Futurism. Though, to give a sense of the range of affinities with his work, his most recent sculptures and collages, obliquely, but most closely, remember the painted/found-object assemblages of American artist Thornton Dial. Yet, what is more crucial to observing the wake of Ovsepyan’s work is to recognize a total transformation of abstraction as mode of artistic production that, following Kandinsky, is focused on the concrete and the im-/mediate—and extending this through the contemporary positions of the archival, the relational, the environmental, the textual, and the autobiographical. Abstraction, for Ovsepyan, is a material process of uncovering synchronicities between formal, physical, psychic, visual, hereditary, and linguistic relations.

Although much of Ovsepyan’s life has been initially guided by histories of Armenian statelessness, personal displacements, and extrinsic politics of his artwork as a Soviet artist operating with a double practice (one of the state, one of his own), intrinsically, the political dimensions of his work are much more subtle and nuanced than a simple rejection of socialist realism or a concerted insurrectionary strategy. In his words, “I only work.” Observably, it is precisely the abandonment of this double practice, when he begins to make only what he wants, and stops taking payments for political murals or propaganda paintings—and, rather, enters the market through his “true” artwork—that his work truly becomes political (as a radical, non-state and anti-market, form of work). In other words, his politicized art was not political, but, rather, dogmatic, representative, and simply fulfilling a professional duty (a form of labor). This is verified by the fact that it was his abstract work, not his explicitly politicized state work, that is targeted and tethered to the political problems with his practice. Therefore, political stakes that emerge from his work are a consequence of the frictions the work itself finds with the surrounding world, and less an intended program of the artist. The politics of aesthetics, the resonances of his artforms, are already-there in the material of the works: their bodies threaten the orders they usurp. The work overtakes the labor. His artwork archives, threads, and molds—an activity of recording a body’s movements without the funneled commentary of a representation, a remark, or a revision. Ovsepyan’s deconstructive practice is one of presentation, demonstration, and preservation of civilizations’ refuse and societies’ fragments, recovering and re-remembering the rejected, cast-out, and the set-adrift along the margins of the continually shifting limits of empire. He builds his view of a stateless metropolis through a hagiography of humanity’s faults, beginning with the ancient strains of Armenian material culture and carrying that history every place he passes-through.

Ovsepyan’s work shows the churning of ideologies, and allow us to listen to the whirring of social or economic machines, without reproducing ideology. Instead, he exposes the components that compose a civilization in an ambiguous state of (de)composition. Despite specific historical markers and particular aesthetic references, each work is left (endlessly) open to interpretation. And this seems to be a fundamental politics of his work: creating openings and building places between borders, between languages, and between moments in time. Ultimately and initially, Ovsepyan appears to be most energetically influenced by his own prolific and unrepentant mode of production. Effortlessly, but industriously, his work springs—wakes—from his work (in the wake of his work...). His work continually cycles. He is constantly moving from one series to the next, always exhausting a particular way of working until it comes to be folded into the next phase. And although each series or body of work has its own peculiarities, it is clear that, sequentially, the central matter of his work is simply the passage of time (and space) consumed by making them. This sense of preserving lost time comes clearly into view in his “mummified” works, eternally resting between here and hereafter (as with the Zaun, Magaxat, and Labyrinth series). Mapping borders between worlds upon the bodies of his work, his art forms a record of a life of displacement. Consuming the refuse of his immigrations—cardboard, newspaper, found objects—his work builds the home he was never permitted to have (using his remains).

At this point, there remains something to be said about the economy of Ovsepyan’s work—and of the broader contexts, consequences, and implications of his historical position as a Soviet, Armenian, German, and American artist. Economically considered, it seems relevant to consider a quiet critique of consumerism strangely coupled with a celebration of the potential for beauty—and connection—through the power of work, of transforming material with a body (and tracking a body’s transformations with material). Almost all of his works created in the United States are made from recycled materials, much of which are collected by his neighbors and brought to him. This serendipitous community collected around his practice through this simple, environmentally conscious activity reveals the relational character emanating from his work. Not only does he construct and deconstruct the semiotic, symbolic, and imaginary relations embedded in societies and exorcised by his works, but he also builds an open social practice bound to the source materials. Regarded as this vortex of relation between bodies, Ovsepyan’s primary medium is the in-between, the gaps between moments in space and time. Consequently, it is, to some extent, ineffectual to consider Ovsepyan’s work through any particular nation-state frame; instead, it is better to find his identity where he encounters himself: at the limit, on the edge of civilization (with a bird’s eye view)….

![Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . 2024-2025. [L.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/fe701d38-fcca-4196-b0cb-23a854f07301/IMG_6243.jpg)

![Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . 2024-2025. [M.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/771ffb72-8bf6-45fc-932e-27e3c2dbbe29/IMG_6244.jpg)

![Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . 2024-2025. [R.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/f553bf12-30a3-4be1-bd8d-ddafa081ead4/IMG_6245.jpg)

![Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . [L: Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/efa3dc30-3433-4ea1-8f8c-ccd87cc1e06c/IMG_6246.jpeg)

![Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . [M: Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/de80697e-39bf-4367-bc54-7dfa54d93d3e/IMG_6247.jpeg)

![Rudik Ovsepyan. Pain Relief . [R: Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/85000d80-0665-454c-9d76-ed1b281fac23/IMG_6248.jpeg)

![Rudik Ovsepyan. Untitled . 2023-2025. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/2fef1951-86a5-49fb-a6d3-5b5e3bf3bbbb/IMG_6316.jpeg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (0). Positioned at gallery-front (right). Oriented forward, facing gallery-penultimate. [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/5936ffde-409a-4251-9a00-0ede4b5498a1/Install+7.jpg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (1). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/3e56001d-ff66-456d-9338-f60d0c5675f9/Install+6+B.jpg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (2). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/df106598-1d1a-4c85-93c1-cbaedb41e77f/Install+5+B.jpg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (3). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/7c223494-1dac-4e1c-b140-2e61fcd4dffe/Install+4+D.jpg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (4). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/83ddb838-70af-4b89-b250-2c98c71f1184/Install+8.jpg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (5). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/65692903-255d-4c2d-a814-0c5035b4f425/Install+9+B.jpg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (6). [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/573257e0-010d-4b00-97b7-0b657c6c1b56/Install+1+B.jpg)

![Sohyong Lee. Deep down Shallow water. 2022. Bookbinding gauze, dictionary, steel, water, video projection loop. [Installation View\ Night.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/b769f0d6-ee72-45cb-a17a-15fd1bc0cd80/Install+11.jpg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (7). Positioned at gallery-penultimate. Oriented toward gallery-front with view of left-hand wall. [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/8ee79f74-c076-464f-8411-a73961426b7c/Install+3.jpg)

![Danica Ribi. Vestige . 2024. Paraffin wax, cellophane, duct tape, paper, bakers racks, pipe clamps, fragment of wall, rags, Virgin Mary. Dimensions variable. [Installation View\ Night.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/64e6dd50-11b4-488e-bad9-f349e9bae062/Install+10+B.jpg)

![Image: Installation View\ Night (7). Positioned at gallery-penultimate. Oriented toward gallery-front with view of right-hand wall; with a partial view of front window. [Photography: Chris Reisig.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/9a1eccea-45d1-4e8b-8eff-1a1fd86b982b/Install+2+B.jpg)

![Rudik Ovsepyan. Sunday, 1976. Tempera and Ink on Paper. 17 x 12 inches unframed (25 x 21 inches framed). [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/c533fc61-4b83-4831-8fbd-dc93d4a0a1ac/RO0.jpg)

![Rudik Ovsepyan. From Home (Memory), 2018. Mixed media on cardboard on plywood. 43 x 35 inches. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/46db43ce-a8bc-4571-8b2b-20cacaaf20df/IMG_2550.jpg)