There's no telling time. Jackie Castillo, Shabez Jamal, Sarah Plummer, Xiao He, Cesar Herrejon, Magaly Cantú. April 13 - May 18, 2024. Group Exhibition.

Jackie Castillo. Through the descent, like the return. 2024. Concrete paver, archival pigment ink, polyester. 12 x 12 x 1.5 inches. Edition 1/3 + 2 AP.

shut

There’s no telling time

Jackie Castillo, Shabez Jamal, Sarah Plummer, Xiao He, Cesar Herrejon, Magaly Cantú

Duration: April 13 – May 18, 2024.

Location: Reisig and Taylor Contemporary (Los Angeles).

Type: Group Exhibition

Release: File

Press: Feature (LA Art Party: April 13, 2024); This Week’s Must-See Art (Curate LA: April 11-17, 2024). LA Art Openings & Spotlight (ArtRabbit: April 10, 2024).

Documentation: Checklist

Topology: Diagram

|

Please contact the gallery with any inquiries:

gallery@reisigandtaylorcontemporary.com

____

____

There’s no telling time. Jackie Castillo, Shabez Jamal, Sarah Plummer, Cesar Herrejon, Magaly Cantú, Xiao He. Reisig and Taylor Contemporary (Los Angeles).

The exhibition is on view from April 13 – May 18, 2024.

….

Organized around experimental techniques of photography, lithography, printmaking, bookmaking, sculpture, performance, video, and drawing, the group exhibition circulates through liminal, in-between materialities and questions of memory (forgetting), timekeeping, recording, and (loss of) language. How is time recorded by a body (a work)? How is time constructed? How is a distance from—or transformation of—space stored and produced by an image? How do I learn to speak my own language (for another)? And how do I take care of the sources and bodies of my work?…. How do I learn to tell time without only being told? There’s no telling. (But there is speaking, making, remembering, and holding (time)….)

With an emphasis on mixing or melding techniques in the process of responding to these questions, the (de)constructively blended mediums and varying social-consciousnesses carried by the works situate the exhibition in-between media, genres, histories, discourses, autobiographies, identities, and afterlives. Working-through decolonial, anti-imperial, intimate, and queer practices, each artwork reconfigures habitual codings of time and space, and different forms of privates and publics, that are lucidly deranged through the unusual forms of “multiples” and imprinted images. Again and again, art histories, family histories, and material histories are seamlessly spoken and spliced-together.

Collectively, the works lovingly, intimately, playfully, and carefully find ways of recording, storing, embodying, occupying, and recollecting by re-telling time through their individually distinct vernaculars—their self-fashioned dialects or homemade mother-tongues. Each work finds a unique articulation of place in time, the place of themselves, according to the distance traveled away from (but also toward) their origins. [1]

Eventually, the exhibition has something to say about keeping records and tracking the world stored in a mark, fragment, trait, image, or piece. The iterative processes included in the exhibition are offered-up as remedies or procedures for dismantling hierarchies by working in errantly but intentionally gathered pieces. Beginning in pieces picked-up along the personal trail of an individual, and asking how someone might use these pieces to build responses to systemic and “universal” problems. In particular, given the colonial-industrial histories embedded in fields like photography and lithography, [2] and the telling tales embedded in all the carefully-selected materials, many of the works definitively break from a tradition (a type of system) if only to return to it through a more ethical approach. By not only implicitly or explicitly critiquing systemic pathologies (for example: extraction economies involved in lithography or the (white-)male-bourgeois gaze built-into photography), but also living-out and showing the present reality of these ways of working with time, iterative processes are extended as a kind of ‘new science’ for unlocking a place between effective technology and affective transformation.

Recalling the recurring question of an artwork’s autonomy versus its reproducibility, the collected iterative processes and the resulting works are presented not simply as ways of copying or reproducing something, but as performances of care for precious, sacred, and irreplaceable (re)sources and the repeated acts of their making. These processes are the production of a vernacular. And the production of a kind of enjoyment…perhaps, even, a joy for the masses (…the joy of the masses?). A shared enjoyment of what is shared. Or a joy that is always here in what is yet to come, and has already happened. [3]

…

Epilogue (Fragment): Techniques of (not) Telling Time

The sequences of repeated actions or steps that make-up processes of producing and developing photographic, lithographic, paginated, recorded, or otherwise (im)printed images lend themselves to questions of timekeeping situated in the relation between material transformations and techniques of the body. Where is time recorded on or by some body? And how does some body record (its passage-through) time? In this case (the casing of the exhibition), techniques of the body could simply be the series of physical movements a body performs in any of these processes: bending, pressing, looking, placing, lifting…. For example, if I am looking at the sculptural works by Shabez Jamal, I see submerged photographs that remain visible through holes made by what looks like repeated attempts to recover an image from the poured concrete that partially covers the film (or I see the film’s refusal to fully sink). With these remaining traces or tracks stored in the concrete, the sculptures record this bodily event (or series of events): some body’s attempts to recover the image (as well as some body’s initial placement of the image into the still-wet concrete). But this history is at the beginning of the works, and these traces, remnants, and holes will continue to shape the possible ways in which the submerged images will be seen—or not—over time. Eventually, the concrete will disintegrate in such a way that the photographs will become visible again. “Concrete denotes urban progress, but in Jamal’s practice we see greater emphasis placed on its entropy. The gradual breakdown of the concrete is inherent to the works themselves, foregrounding the passage of time with the understanding that eventually all of the lives within the photographs will once again be made visible.” (Excerpt from exhibition text for “Close your eyes, and remember”—Jamal’s solo exhibition with Sibyl Gallery in New Orleans.)

Recording the lifetimes concealed by the concrete at the same time as enacting the ‘lifetime’ of the sculptures as material objects, the pieces act-out a history that moves backwards and forwards at the same time—making-room for the possibility of revisiting what has happened from a different perspective, at a different point in time. (Is the video performing a similar retelling of time (and space) between social, bodily, and im/material histories?)

Or, techniques of the body might also be the more in-between ‘steps’ of infusing the resulting forces of these repeated “techniques” or movements into the materials: the traces, marks, or remainders. This sort of process also seems to be underway in Jamal’s sculptural works: eventually, the concrete will disintegrate in such a way that the photographs will become visible again. Between Jamal’s initial act or performance of placing the photograph in a concrete cast, and the errant, eventual ‘erosion’ of the concrete covering the image, time is (in)fused between the two bodies at work. (Time is fused between what has already happened in order to produce the object, and as what will take place throughout the object’s lifetime (within and beyond the timeframe of the exhibition).)

Or, if I examine Sarah Plummer’s paper sculptures, I encounter different—but similar kind of—infusions (of time) giving way along every dimension of these residual little works. The supple indentations, embedded fragments, and ambiguous impressions that line the curvature of these extra terrestrial—that is, “extra” as in more—objects remember the pressure of the body against which these sculptures were nomadically formed over time. (The works wandered with the artist.) If I were to find these outside of the gallery, I would probably have no idea as whether they are very old or very new objects—in either cases, the pieces appear at the limits of time. (A möbius, non-orientable timeline….) But at the same time the indentations remind me that they were also formed at the limits lapping a body: pressed and held but eventually, and with some kind of ambiguous ceremony, let-go or spat-out…. The limits of time and the limits of a body appear at the same place and in the same instant. A history is performed and kept in motion so the artwork never becomes an artifact (or an artifice).

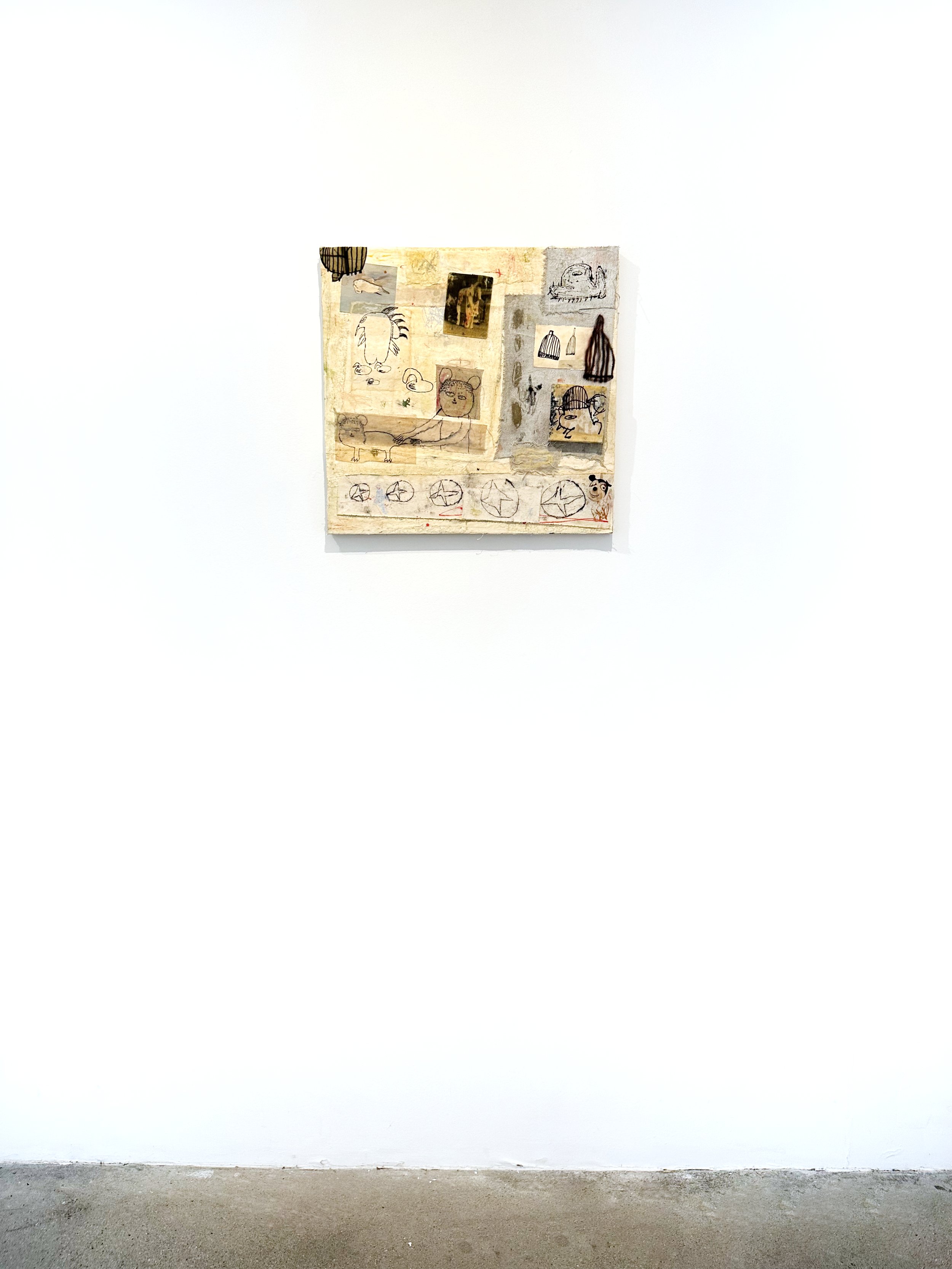

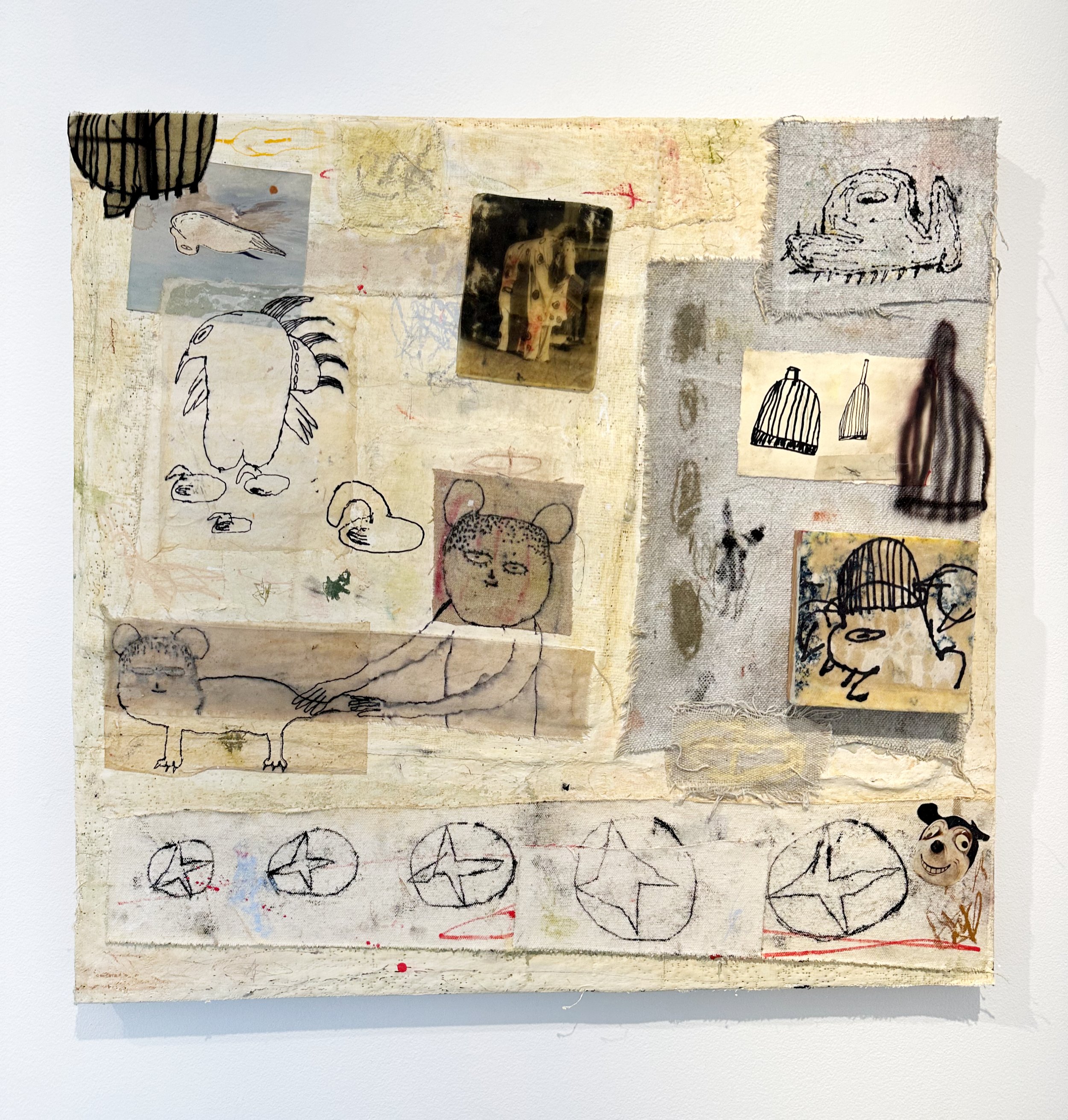

This synchronization of a body’s limits with time (in terms of a sequence bodily movements) is also repeated in the relationships with the formal composition of the three(-or-four) different “artist books” included in the exhibition: Cesar Herrejon’s collapsible wall-piece “How We Were Born II”(2023) (and his “Untitled Images” (2024) installation); Xiao “He’s The Yellow Wallpaper” (2023); and Magaly Cantú’s “Greñuda” (2024). Each of these works literalizes the sequential time embodied in the previously mentioned works with processions of parts that connect in order to form a (w)hole. However, unlike the prior works, which condense this “sequence of bodily movements” into a singular (but shifting) object or state that obscures or conceals this temporality, these works unfold this condensation and present a synchronic—‘at-the-same-time’—view of the diachronic—‘one-after-another’—parts as either bound wholes or congealed spreads. In other words, their pagely or otherwise fragmentary forms ask for a body to ‘flip-through,’ act-out, or recreate this sequential, cycling time by actively reading or looking-through or along the object itself. The relations between the artist, the artwork, and the observer are involuted or turned inside-out. This time, I form the connections between (my) body, the object, and the body of an other (the artist). As with Herrejon’s “Untitled Images” collage of xerox transfers (onto silicon caulking), I am left to pick-up the pieces and install myself among the remains. The sepia toned slabs of translucent silicon pucker under their weight against the rusty nails clasping each piece on the wall, with foggy images peering-through from a distance that resembles a bad memory remembered fondly. (After all, it’s arguable that all family photos are bad memories, or at least memories so intentionally made that they become imagination.) Or a good memory remembered badly—or barely. Or maybe I’m just thinking of an episode from a TV show or a meme I almost made and I end-up mistaking that for my own memory. Either way, I find myself forgetting what I remember as soon as I assume someone put any of these images together for a reason. Or maybe memory is what holds them in-place, not where they came from….

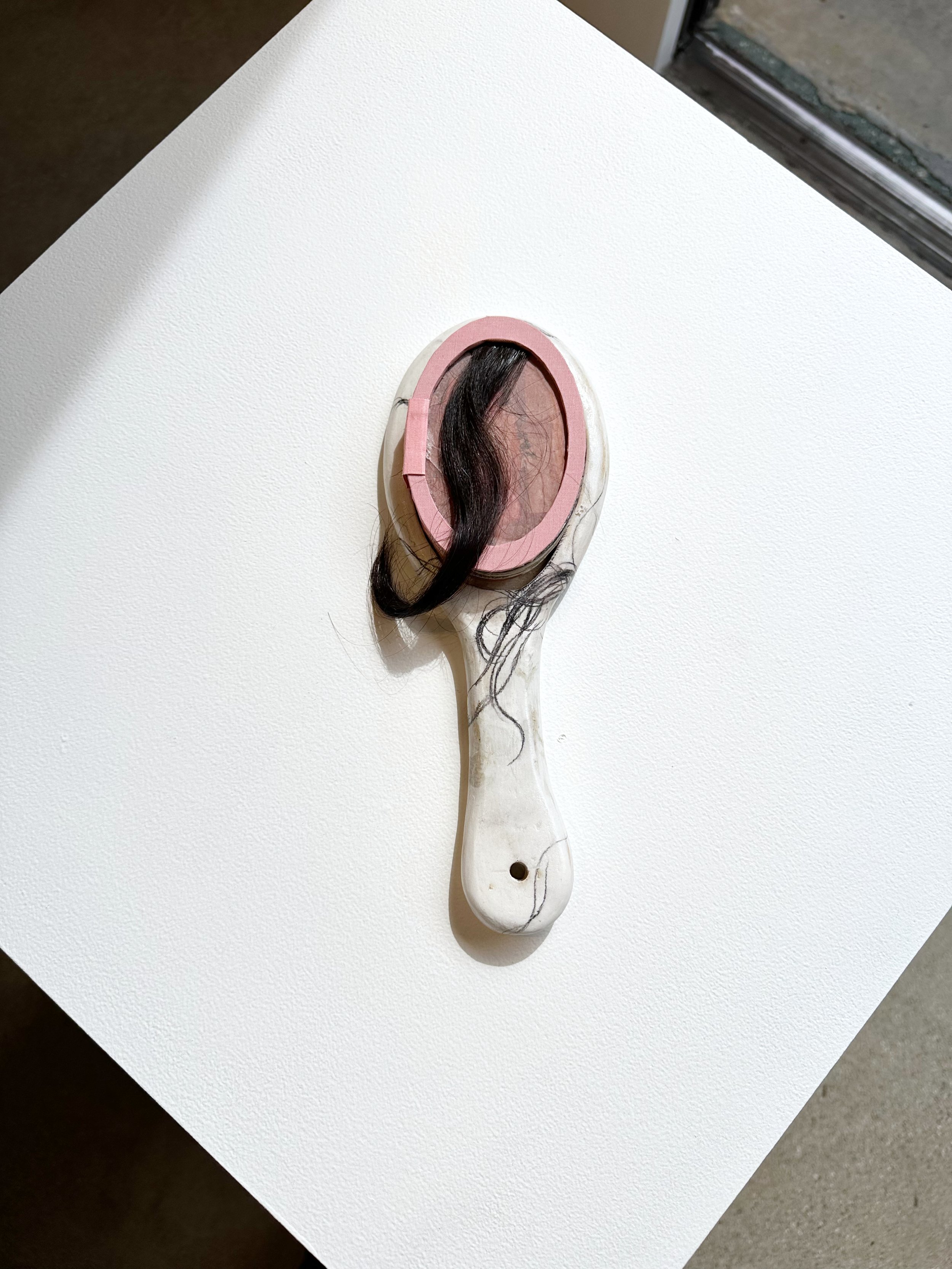

With Cantú’s ceramic mirror-brush-book “Greñuda”, a slightly curled lock of (the artist’s) brown hair bookmarks the front-cover, which subtlely displays what appears to be a screen-printed photography of the artist as a child. And the following series of cropped, close-up or partial views show hair in different positions and various domestic scenes of bodily care: eyelashes; a braided lock; hair gathering on the floor of a bathtub near the drain. With each view I am nearer-to or farther-from (the hair), getting closer as I move towards the end of the book (and farther from the piece of human hair on the front cover). Farther from the body and closer to the image, or closer to the body and obscuring the (actual) image (i.e., the photograph of the artist of the child, as well as the entire book of images (as a cover).) Each view reveals a different intimacy between a body and its hair—and between my gaze, my own body, and the body of another. (The cropped perspective makes it feel as if I am stepping-into the view offered in each image.)

Near-to but distanced-from this work is Xiao He’s “The Yellow Wallpaper”: a book referring to the Victorian-era short story (1892) by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Through a series of (fictional) journal entries, the short-story provides glimpses of a room adorned with yellow wallpaper through a woman’s progressively evolving hallucinations she experiences while suffering from a postpartum “hysteria.” Like the progression of the imagery in the short-story, the drawings in the book further collapse the distance between the figure or body of the woman and the pattern on the yellow wallpaper, with which she seems to become increasingly obsessed. This progressive collapse of what the woman is looking at—the object of her gaze—onto the surface of her body acts-out the gap between what is seen, what is said, and what is made. (It is in this gap that the works find some body.) (Though, “what is said” is not always fully articulated by any of the works. The inclusion of text in He’s book likely suggests that something is being said, but the words are coming from somewhere else and ultimately the narrative is formed through the sequential relation of the images more so than the text itself (as if the words are breaking the narrative, filling-up the gaze with language and blocking its view.) And with Jamal’s video work we most literally get speech, “what is said,” but only in passing and in ways that seem so intimate to their source that whatever is being said warns us that we might not be meant to hear the words. Maybe these works are recording more than saying. In either case, there’s no telling “what is said” but we nevertheless find a narrative…in time….)

Working with the gaze—as well as reading, writing, and moving—as a technique of the body and therefore as dimension of time in terms of movement, change, and transformation (as well as (projective-perspective) space) is an activity shared by all of the works in their refusal of an instantaneous encounter: each work either lapses or is elapsed. The ‘time’ is built into and made visible in the material bodies of the works but is not necessarily immediately accessible (and when it is—as with the books which cause us to embody the temporality by flipping-through the pages—I can only access that time through the works’ relations to my own body and memory). Once again, the timing and timekeeping of the work occur as a body passes along its limits. And along the limits of the gaze.

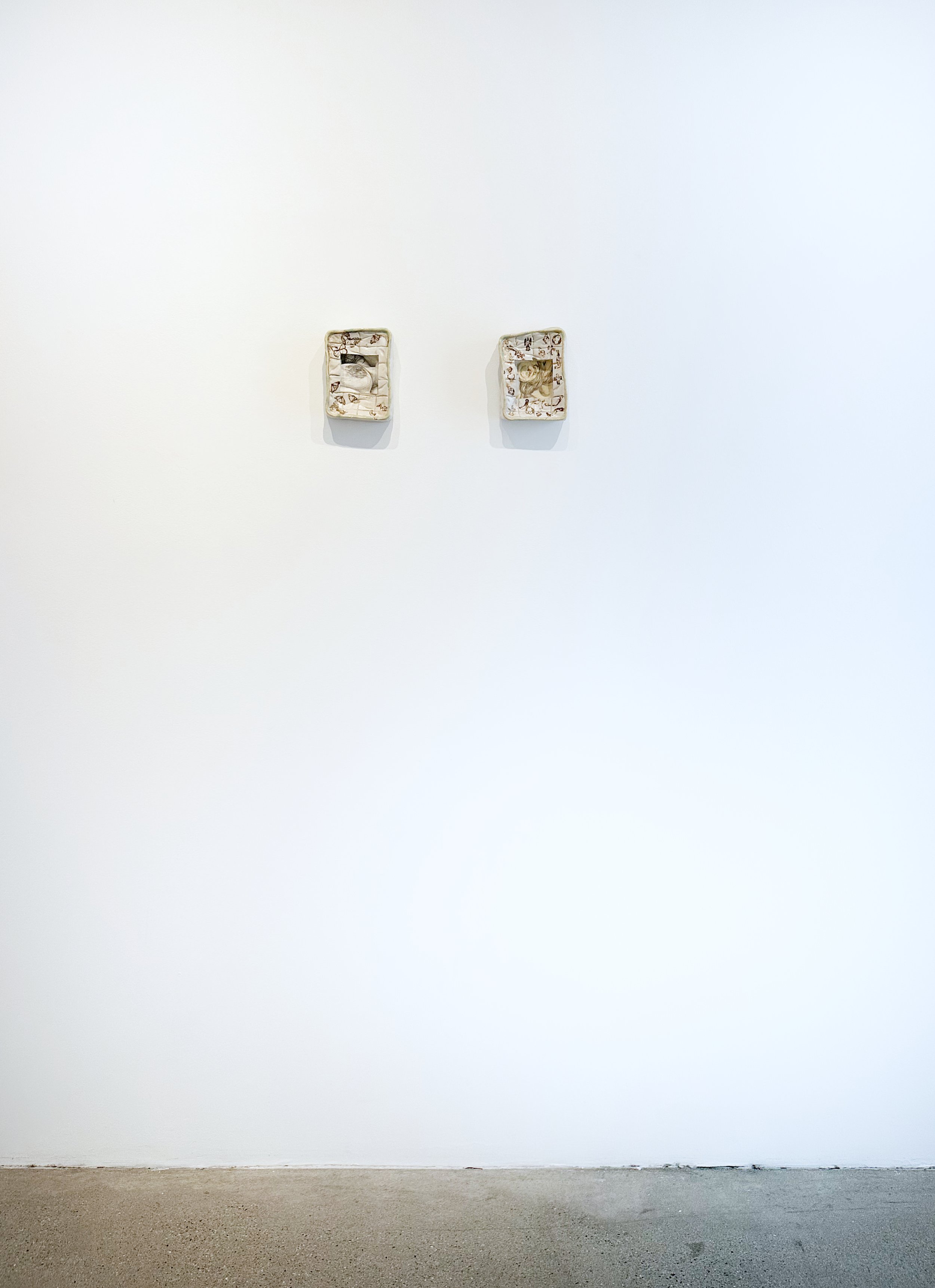

Looking along an impossible gaze pressed between a body and the broken bed that gathers against its gravity, “Mi Camita Quebrada” arrives at the navel of a dream—at a seductive seam eclipsed by sleep… by a body falling into fabric. The windowed view cut-out of the supple ceramic frame remembers the obvious voyeurism of looking into someone else’s bed(room) and catching a glimpse of the flesh intimated only to the privacy of their prone position. (Somehow I’m allowed to see between the sheets.) —But then the whimsical marks—the butterflies and little milagros adorning the ceramic surfaces—remind me that this intimacy is only offered between the body and the mattress, between the (self-)image and the vessel that breaks beneath (or above) its weight. The intimacy of somewhere a body can be without being seen, a nightly return to the lack of the gaze(…still looking nonetheless). (Time to close the window…).

This activity of recording time, and specifically a recording as something that connects (re-cords) close-by but otherwise distanced perspective or events, is particularly evident in the three pieces in the paver series by Jackie Castillo. The three rebar-mounted works from Castillo’s paver series are photographic double exposures of the distinctively ‘southern California’ yard-spaces found between the sidewalk and homes throughout much of this region. The documentation of this interstitial space—between the (private) domestic space and the (public) roadway or pedestrian walkways—records these yard spaces from the perspective of walker or passer-by, or as someone on the limits of (both of) these spaces. The photographs are editioned as archival pigment prints on polyester adhered to the concrete paver. The technical double exposure engineered through each image is repeated across the different types of contrasting doubled scenes ‘exposed’ by the resulting photograph. Specifically, each work combines, in varying degrees, fading views of natural greenery, urban domestic architectures, and objects or traces suggestive of human transformations of—seemingly that—space (…the watering can and shovel visible in “Of the garden just risen from the darkness” (2024)). Positioned at the center of each piece is some place furnished by and for a body’s passage: an entryway, a stairway, an armchair. (And each of these ‘passages’ ends up detoured, interfered-with, or blocked: a garden passage leads to tools of labor or recreation, a grove of trees grows in the stairway, a graffiti-figure finds its wall or window reflection passing-through the chair.) Along this layering of growths, (external) domestics, industrials, and decays, the mixed views also display subtle but certain distinctions of the disparate class-positions echoed by the duplicity of a yard as a place of enjoyment as well as a site of labor, and, like any aspect of a home, a site reflective of someone’s labor (and income). Ultimately and initially, the paver stones themselves also find a transformative connection to the masonry material in relation to labor histories of Latinx and migrant workers in the region.

…Working along the borders between an individual body and collective memory or consciousness, the artworks in this exhibition seem to come between these places of the personal and the systemic by keeping time without telling it (without reproducing what it already is)… timekeeping with a special relativity. Time is worked with as relation between materials and bodies—as the materiality of limits and betweens. The liminal mixed-media and experimental mixed-techniques observed, heard, smelled, and touched in-and-between each work echoes this borderland by taking-shape between distinct mediums. [To be continued….]

__________

[1] The title of the exhibition is itself an inherited expression or vernacular phrase: it’s something my grandmother always use to say in response to change—“There’s no telling time.”

[2] More specifically, many of the chemical or industrial components used at various stages—from acquisition, to manufacture, to use-consumption—of photographic and lithographic processes are based in the extraction of resources from areas and peoples historically subjected to settler-colonization or imperial (externally domineering) manipulations of indigenous materials for economic purposes realized elsewhere (to the advantage of others). For example, gum arabic (a material used as in food, as well as in lithography and, historically (beginning in 1855), in photography for gum bichromate prints) is a natural resource produced with sap taken from types of the Acacia tree commonly found in the Sahel region of Africa, and especially Sudan. So far, despite the massive international circulation of this material, there has been no observable domestic gains from the over-development of this extraction-economy engineered to suit external demand.

[3] Or, as one of the artists says, a “proletariat joy.” (Thank you Jackie Castillo for infecting me with this phrase.)

____________________

Bios

:

Jackie Castillo is a Los Angeles-based artist working in sculpture, installation, and film photography. Her practice is rooted in examining the isolation and anxiety felt by the working class by investigating the relationship between infrastructure, urban development, and collective memory. Utilizing the visual vernacular of surface, material, and ruins, she examines how an internalized loss of identity may render the self as unreal, estranged, and in various states of invisibility. Her work has been exhibited at The California Museum, The Long Beach Museum of Art, The Mistake Room, the 2022 New Wight Biennial at UCLA Broad Art Center, Charlie James Gallery, As-is Gallery, the Mexican Center for Culture and Cinematic Arts, View/Paul Soto Gallery, and the Material Art Fair in Mexico City. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art has acquired her work Turning No.2 as part of the permanent collection. She was awarded the 2021 Individual Artist Fellowship by the California Arts Council.

|

Donny Bradfield, also known as Shabez Jamal, is an interdisciplinary artist and educator residing in New Orleans, LA. Born in 1992 in St. Louis, Jamal earned their BA from the University of Missouri - St. Louis and their MFA from Tulane University of Louisiana. Their artistic practice explores memory as it relates to physical, political, and socio-economic spaces. Jamal has received numerous fellowships and awards, including Harvard University’s In the City Fellowship, the Mellon Community Engaged Fellowship, and Washington University’s The Divided City Research Grant. Their work has been displayed in various national and international art spaces, such as the St. Louis Art Museum, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, the Baltimore Museum of Art, and the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt. Their work is part of the St. Louis Community College and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art collections, as well as several private collections.

|

Sarah Plummer is a collaborative printer, maker, and writer, lately of Australia and more recently of California. She was raised in Sydney and moved to the USA to pursue a Bachelor of Fine Arts (Printmaking) at Rhode Island School of Design before attending Tamarind Institute’s Professional Printer Training Program for collaborative lithography. She has worked on fine-art prints at Wingate Studio, Gemini G.E.L. and for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 150th anniversary. Within the last year, she has been operating her own collaborative studio, Speck Editions, on unceded Tongva/Gabrielino land—in Los Angeles. Sarah is captivated by the alchemic expanse of lithography and loves things that seem impossible. While she finds the opportunity to bring well-honored, innovative approaches to artists and their work as one of the greatest pleasures, her work—print and otherwise—leads an investigation into land, memory, material, grief, love, and freedom.

|

Cesar Herrejon is currently an MFA candidate at the University of Colorado Boulder focusing on mixed media painting and drawing. He is from Birmingham Alabama. Growing up in the deep south, Cesar was involved in the skateboard culture around his teen years and draws influences from these childhood experiences into his work. Currently his work also explores materials foreign to academic artistic expression that parallel and enrich his cultural heritage. He often uses defamiliarized quotations from culture in his work like the surrealism that he finds deeply rooted in Mexican Culture. Art is the only thing that has interested him, and it is the only thing he has found to feel passionate about and build his identity with. His studies and research included printmaking incorporating it with painting and drawing.

|

Magaly Cantú is an interdisciplinary artist based in Denton, Texas. She works between a traditional printmaking, drawing and expanded ceramic practices. Through the translation of familial relationships, personal memories, photographs and daydreams. Magaly dissects experiences of girlhood as a Latina an the impacts of navigating in-between tradition and modernization. Magaly has shown work at Arts Fort Worth, 500X Gallery, the University of West Virginia, and the K Space Contemporary. Her work has also been added to multiple collections such as Marais Press print collection at The Hilliard Art Museum and Incisori Contemporanei, Villa Benzi Zecchini, in Caerano di San Marco, Italy. She is currently an M.F. A candidate specializing in printmaking, at the University of North Texas.

|

Xiao He (b. 1998, Chengdu, China) is a multidisciplinary artist currently based in San Francisco. Xiao holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a master’s degree from Carnegie Mellon University. Xiao’s works have been exhibited internationally, including 2022 Art Capital (Paris, France), 2021 Biennale di Genova (Genoa, Italy), Upstream Gallery (New York, USA), Huacui Contemporary Art Center (Shanghai, China) and Zhou B Art Center (Chicago, USA). Her artist interviews have been featured on Al-Tiba9 Art Magazine, VoyageLA, and Vogue China, along with residencies awarded at the Cubberley Artist Studio Program (2024) and Kala Art Institute (2023). Her mixed media artists’ book A Collection of Random Thoughts is now part of the permanent collection of Joan Flasch Artists’ Book collection in Chicago. Xiao is also a member of Oil Painters of America and served on the Apex Art New York jury panel.

____________________

{Biographical texts courtesy of the artists.}

Installation View\ Night (0).

Installation View\ Night (1).

Installation View\ Night (2).

Installation View\ Night (3).

Installation View\ Night (4).

Installation View\ Night (5).

Installation View\ Night (6).

Installation View\ Night (7).

Installation View\ Night (8).

Installation View\ Day (0).

Shabez Jamal. {Video installed on monitor} Like Home (Anita and the Tambourine Man). 2022. Experimental Video. {Foreground}: {Left} Untitled 02. 2023. Type-I instant film and poured concrete. 2.25 x 12 x 9.25 inches. {Right} Untitled 04. 2023. Type-I instant film and poured concrete. 2.25 x 12 x 9.25 inches.

Shabez Jamal. {Video installed on monitor} Like Home (Anita and the Tambourine Man). 2022. Experimental Video. {Foreground}: {Left} Untitled 02. 2023. Type-I instant film and poured concrete. 2.25 x 12 x 9.25 inches. {Right} Untitled 04. 2023. Type-I instant film and poured concrete. 2.25 x 12 x 9.25 inches.

Shabez Jamal. {Left} Untitled 02. 2023. Type-I instant film and poured concrete. 2.25 x 12 x 9.25 inches. {Right} Untitled 04. 2023. Type-I instant film and poured concrete. 2.25 x 12 x 9.25 inches.

Shabez Jamal. {Above} Untitled 02. 2023. Type-I instant film and poured concrete. 2.25 x 12 x 9.25 inches. {Below} Untitled 04. 2023. Type-I instant film and poured concrete. 2.25 x 12 x 9.25 inches.

Shabez Jamal. Untitled 02. 2023. Type-I instant film and poured concrete. 2.25 x 12 x 9.25 inches.

Shabez Jamal. Untitled 04. 2023. Type-I instant film and poured concrete. 2.25 x 12 x 9.25 inches.

Installation View\ Day (1).

Magaly Cantú. Greñuda. 2024. Ceramic frame, transparent flax paper, human hair; lithography, screen printing. Approx. 15 x 4 x 2 inches.

Magaly Cantú. Greñuda. 2024. Ceramic frame, transparent flax paper, human hair; lithography, screen printing. Approx. 15 x 4 x 2 inches. [Open.]

Magaly Cantú. Greñuda. 2024. Ceramic frame, transparent flax paper, human hair; lithography, screen printing. Approx. 15 x 4 x 2 inches. [Back.]

Installation View\ Day (2).

Xiao He. The Yellow Wallpaper. 2023. Colored pencil on Dura-Lar film, Bradbury & Bradbury Wallpaper; Victorian photo frame binding. Text from The Yellow Wallpaper, short story by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1892). 2.75 x 3.75 x 1.5 inches.

Xiao He. The Yellow Wallpaper. 2023. Colored pencil on Dura-Lar film, Bradbury & Bradbury Wallpaper; Victorian photo frame binding. Text from The Yellow Wallpaper, short story by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1892). 2.75 x 3.75 x 1.5 inches.

Xiao He. The Yellow Wallpaper. 2023. Colored pencil on Dura-Lar film, Bradbury & Bradbury Wallpaper; Victorian photo frame binding. Text from The Yellow Wallpaper, short story by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1892). 2.75 x 3.75 x 1.5 inches.

Cesar Herrejon. How We Were Born I. 2023. Fabric, ink, graphite on individual plaster grounds. 16 x 10 inches.

Cesar Herrejon. How We Were Born I. 2023. Fabric, ink, graphite on individual plaster grounds. 16 x 10 inches.

Cesar Herrejon. How We Were Born I. 2023. Fabric, ink, graphite on individual plaster grounds. 16 x 10 inches. [Detail.]

Cesar Herrejon. How We Were Born I. 2023. Fabric, ink, graphite on individual plaster grounds. 16 x 10 inches. [Detail.]

Installation View\ Day (3).

Sarah Plummer.

Sarah Plummer. {Left-Right} Maskros. 2024. Kozo, gifted turritella agate, sandalwood dye, ruby shellac, dandelion florets (34.10675°N 118.29621°W). 6 x 4.3 x 1 cm. Lime kiln damstone. 2024. Kozo, midorimenou iwa-enogu (a natural mineral pigment made from ground bloodstone), found ceramic tile, Black Wattle gum (38.89422°S, 150.50305°E). 6 x 4.2 x 0.6 cm. the place where there will always be water (Payahuunadu damstone). 2024. Kozo, found rock (35.96951°N, 117.90878°W), iwashudo (red marble) pigment, matsuba rokusho (malachite) pigment, indigo dye, Black Wattle gum (38.89422°S, 150.50305°E). 4.5 x 6.2 x 0.6 cm.

Sarah Plummer. Maskros. 2024. Kozo, gifted turritella agate, sandalwood dye, ruby shellac, dandelion florets (34.10675°N 118.29621°W). 6 x 4.3 x 1 cm.

Sarah Plummer. Lime kiln damstone. 2024. Kozo, midorimenou iwa-enogu (a natural mineral pigment made from ground bloodstone), found ceramic tile, Black Wattle gum (38.89422°S, 150.50305°E). 6 x 4.2 x 0.6 cm.

Sarah Plummer. the place where there will always be water (Payahuunadu damstone). 2024. Kozo, found rock (35.96951°N, 117.90878°W), iwashudo (red marble) pigment, matsuba rokusho (malachite) pigment, indigo dye, Black Wattle gum (38.89422°S, 150.50305°E). 4.5 x 6.2 x 0.6 cm.

Sarah Plummer. {Left-Right} Rusty Carrot House. 2024. Kozo, found shard, Sydney Rusty Gum kino (33.98354°S, 151.05673°E), Black Wattle gum (38.89422°S, 150.50305°E). 6.8 x 4.9 x 6 cm. Wonny. 2024. Kozo, cotton, plant matter, turmeric (gifted), collaged lithographic fragments, shell (31.45879°S, 152.93376°E), Bunya Pine resin (33.8365° S,151.15579°E), Black Wattle gum (38.89422°S, 150.50305°E). 9.8 × 5.2 x 5.7 cm. a sun buried a thousand years ago and dug up only yesterday. 2024. Kozo, bottle brush flowers (33.97280°S, 151.05071°E), turmeric (gifted), vintage cotton (gifted), Black Wattle gum (38.89422°S, 150.50305°E). 7.2 x 5.8 x 4.1 cm (5.8 cm depth with fabric).

Sarah Plummer. Rusty Carrot House. 2024. Kozo, found shard, Sydney Rusty Gum kino (33.98354°S, 151.05673°E), Black Wattle gum (38.89422°S, 150.50305°E). 6.8 x 4.9 x 6 cm.

Sarah Plummer. Wonny. 2024. Kozo, cotton, plant matter, turmeric (gifted), collaged lithographic fragments, shell (31.45879°S, 152.93376°E), Bunya Pine resin (33.8365° S,151.15579°E), Black Wattle gum (38.89422°S, 150.50305°E). 9.8 × 5.2 x 5.7 cm.

Sarah Plummer. a sun buried a thousand years ago and dug up only yesterday. 2024. Kozo, bottle brush flowers (33.97280°S, 151.05071°E), turmeric (gifted), vintage cotton (gifted), Black Wattle gum (38.89422°S, 150.50305°E). 7.2 x 5.8 x 4.1 cm (5.8 cm depth with fabric).

Installation View\ Day (4).

Installation View\ Day (5).

Installation View\ Day (6).

Installation View\ Day (7).

Installation View\ Day (8).

Installation View\ Day (9).

Magaly Cantú.

Magaly Cantú. Cierra la Ventana. 2023. Lithography, collage. 20 x 26 inches (framed). [Photo Credit: Finlay Markham.]

Magaly Cantú. Cierra la Ventana. 2023. Lithography, collage. 20 x 26 inches (framed). [Photo Credit: Finlay Markham.]

Magaly Cantú. Mi Camita Quebrada, 1/3 {Left} & 2/3 {Right}. 2022. Porcelain slip casting, screen printing, cotton batting, graphite on paper. 7 x 5.5 x 2 inches each.

Magaly Cantú. Mi Camita Quebrada, 1/3 {Left} & 2/3 {Right}. 2022. Porcelain slip casting, screen printing, cotton batting, graphite on paper. 7 x 5.5 x 2 inches each.

Magaly Cantú. Mi Camita Quebrada, 1/3. 2022. Porcelain slip casting, screen printing, cotton batting, graphite on paper. 7 x 5.5 x 2 inches.

Magaly Cantú. Mi Camita Quebrada, 2/3. 2022. Porcelain slip casting, screen printing, cotton batting, graphite on paper. 7 x 5.5 x 2 inches.

Installation View\ Day (10).

Cesar Herrejon. Nimix and His Creature. 2023. Fabric, ink, soft pastels, watercolor crayons, plaster on wood. 20 x20 inches.

Cesar Herrejon. Nimix and His Creature. 2023. Fabric, ink, soft pastels, watercolor crayons, plaster on wood. 20 x20 inches.

Cesar Herrejon. Nimix and His Creature. 2023. Fabric, ink, soft pastels, watercolor crayons, plaster on wood. 20 x20 inches. [Detail.]

Installation View\ Day (11).

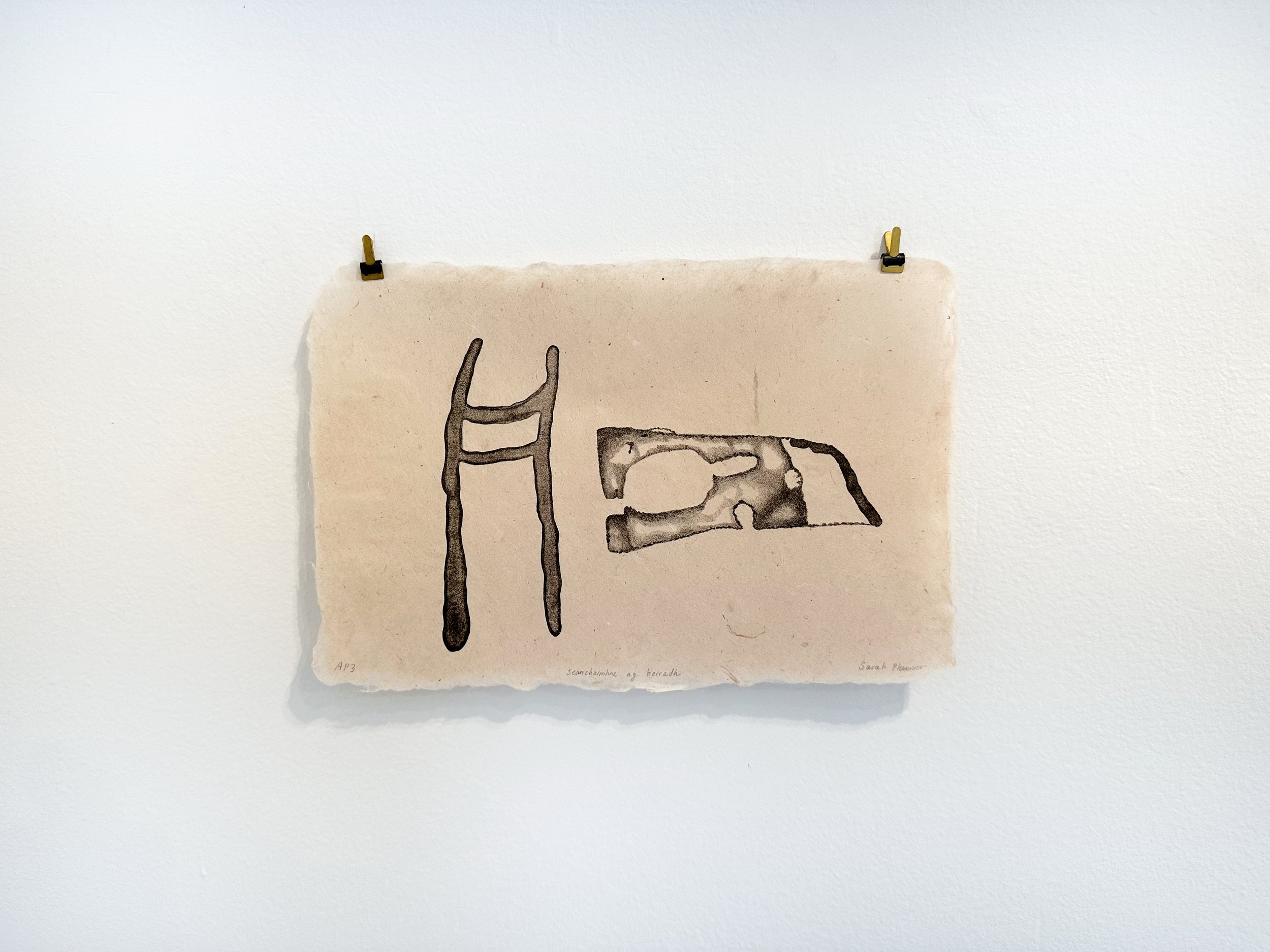

Sarah Plummer. {Left} seanchuimhne ag borradh. 2024. Stone lithograph. Variable Edition of 19 + Artist's Proofs. 8.75 x 5.75 inches. A.P. 3 printed on Handmade washi. {Right} If you leave it alone, it might just happen. 2022. Stone lithograph. Edition of 28 + Artist's Proofs. 7.5 x 9.5 inches. B.A.T. (bon à tirer) printed on (Okawara Select 51g/m2).

Sarah Plummer. seanchuimhne ag borradh. 2024. Stone lithograph. Variable Edition of 19 + Artist's Proofs. 8.75 x 5.75 inches. A.P. 3 printed on Handmade washi.

Sarah Plummer. If you leave it alone, it might just happen. 2022. Stone lithograph. Edition of 28 + Artist's Proofs. 7.5 x 9.5 inches. B.A.T. (bon à tirer) printed on (Okawara Select 51g/m2).

Jackie Castillo.

Jackie Castillo. {Left-Right} Of the garden just risen from darkness. 2024. Concrete paver, archival pigment, ink, polyester. 12 x 12 x 1.5 inches. And once more I remember. 2024. Concrete paver, archival pigment, ink, polyester 12 x 12 x 1.5 inches. Through the descent, like the return. 2024. Concrete paver, archival pigment, ink, polyester. 12 x 12 x 1.5 inches.

Jackie Castillo. Of the garden just risen from darkness. 2024. Concrete paver, archival pigment, ink, polyester. 12 x 12 x 1.5 inches.

Jackie Castillo. Of the garden just risen from darkness. 2024. Concrete paver, archival pigment, ink, polyester. 12 x 12 x 1.5 inches. [Side.]

Jackie Castillo. And once more I remember. 2024. Concrete paver, archival pigment, ink, polyester 12 x 12 x 1.5 inches.

Jackie Castillo. And once more I remember. 2024. Concrete paver, archival pigment, ink, polyester 12 x 12 x 1.5 inches. [Side.]

Jackie Castillo. Through the descent, like the return. 2024. Concrete paver, archival pigment, ink, polyester. 12 x 12 x 1.5 inches.

Jackie Castillo. Through the descent, like the return. 2024. Concrete paver, archival pigment, ink, polyester. 12 x 12 x 1.5 inches. [Side.]

Jackie Castillo.

Jackie Castillo. From Somewhere They Had Known Before. 2023. Concrete landscape edger, 120mm film scan of the Great Pyramid of Cholula, laser print, polyvinyl acetate aadhesive. [Aerial.]

Jackie Castillo.Jackie Castillo. From Somewhere They Had Known Before. 2023. Concrete landscape edger, 120mm film scan of the Great Pyramid of Cholula, laser print, polyvinyl acetate aadhesive. [Orthogonal.]

Installation View\ Afternoon (0).

Installation View\ Afternoon (1).

Installation View\ Day (15).

Cesar Herrejon. Untitled Images. 2024. Xerox transfer on caulk. 23 x 19 inches.

Cesar Herrejon. Untitled Images. 2024. Xerox transfer on caulk. 23 x 19 inches.

Cesar Herrejon. Untitled Images. 2024. Xerox transfer on caulk. 23 x 19 inches. [Detail.]

Cesar Herrejon. Untitled Images. 2024. Xerox transfer on caulk. 23 x 19 inches. [Detail.]

![Magaly Cantú. Greñuda. 2024. Ceramic frame, transparent flax paper, human hair; lithography, screen printing. Approx. 15 x 4 x 2 inches. [Open.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/afbdf02b-3864-4589-ad87-6557216d9eca/Cantu_Grenuda_2.jpg)

![Magaly Cantú. Greñuda. 2024. Ceramic frame, transparent flax paper, human hair; lithography, screen printing. Approx. 15 x 4 x 2 inches. [Back.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/5f4292e0-781e-4f68-9c18-6c51fd53a6f5/Cantu_Grenuda_3.jpg)

![Cesar Herrejon. How We Were Born I. 2023. Fabric, ink, graphite on individual plaster grounds. 16 x 10 inches. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/3bed3829-a41f-4c77-b4d8-17ee3cbac71f/Herrejon_How_3.jpg)

![Cesar Herrejon. How We Were Born I. 2023. Fabric, ink, graphite on individual plaster grounds. 16 x 10 inches. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/9dae1e40-ab8d-4905-8bd3-ccd48146d777/Herrejon_How_1.jpg)

![Magaly Cantú. Cierra la Ventana. 2023. Lithography, collage. 20 x 26 inches (framed). [Photo Credit: Finlay Markham.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/4a1d73d9-2b64-4a88-b250-ce369aa35589/RTC10.jpg)

![Magaly Cantú. Cierra la Ventana. 2023. Lithography, collage. 20 x 26 inches (framed). [Photo Credit: Finlay Markham.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/227b8652-1830-435c-8ea4-0bdd7586f49b/RTC9.jpg)

![Cesar Herrejon. Nimix and His Creature. 2023. Fabric, ink, soft pastels, watercolor crayons, plaster on wood. 20 x20 inches. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/6d1d9036-b502-49a0-9afb-c468a8d653aa/Herrejon_Nimix_3.jpg)

![Jackie Castillo. Of the garden just risen from darkness. 2024. Concrete paver, archival pigment, ink, polyester. 12 x 12 x 1.5 inches. [Side.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/9e382969-9c50-40d6-9358-6c84fdc63d42/Castillo_Of+the+garden_2.jpg)

![Jackie Castillo. And once more I remember. 2024. Concrete paver, archival pigment, ink, polyester 12 x 12 x 1.5 inches. [Side.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/9ada58fb-37b6-4795-aac4-6a1759f9e7ed/Castillo_And+once_2.jpg)

![Jackie Castillo. Through the descent, like the return. 2024. Concrete paver, archival pigment, ink, polyester. 12 x 12 x 1.5 inches. [Side.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/77fbdc6c-763f-4905-a5cb-18469cfa3d0b/Castillo_Through_2.jpg)

![Jackie Castillo. From Somewhere They Had Known Before. 2023. Concrete landscape edger, 120mm film scan of the Great Pyramid of Cholula, laser print, polyvinyl acetate aadhesive. [Aerial.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/849962f0-681e-428c-b1e9-9844d6e8f661/castillo_From+Somewhere_2.jpg)

![Jackie Castillo.Jackie Castillo. From Somewhere They Had Known Before. 2023. Concrete landscape edger, 120mm film scan of the Great Pyramid of Cholula, laser print, polyvinyl acetate aadhesive. [Orthogonal.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/47970dc0-3c5e-4302-98a4-aa8ee7cef036/castillo_From+Somewhere_1.jpg)

![Cesar Herrejon. Untitled Images. 2024. Xerox transfer on caulk. 23 x 19 inches. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/4c2b1680-cd56-41f5-a8aa-2f7e52e84746/Herrejon_Xerox_4.jpg)

![Cesar Herrejon. Untitled Images. 2024. Xerox transfer on caulk. 23 x 19 inches. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/7c577e8c-7cae-44a4-8803-a1e6dac9b0fe/Herrejon_Xerox_3.jpg)