spleen iiiii. Allison Arkush, Maccabee Shelley, Luc Trahand, Sinclair Vicisitud. July 27 - September 7, 2024. Group Exhibition.

Maccabee Shelley. Memory. 2024. Cast glass and electronics.

SHUT

spleen iiiii

Allison Arkush, Maccabee Shelley, Luc Trahand, Sinclair Vicisitud

Duration: July 27 – September 7, 2024.

Location: Reisig and Taylor Contemporary (4478 W Adams Blvd, Los Angeles)

Type: Group Exhibition.

Release: File; Curate LA; Artforum.

Supplements: Humdrum (Sound/Text Installation) Statement by Luc Trahand, link to project.

Press: The Best of Art in Los Angeles: Fall 2024 (Curate LA: September 4, 2024); This Week’s Must-See Art (Curate LA: July 25-31, 2024).

Documentation: Checklist. Epilogue: A Scribble. A Spiral.

Topology: Diagram.

|

Event: Press Release

— Epilogue: A Scribble. A Spiral. Saturday, September 7, 6:30pm - 9pm. Closing Reception with Performance of Humdrum reading by Luc Trahand, followed by a screening of the film Spiral Jetty by Robert Smithson.

|

Please contact Emily Reisig with any inquiries:

gallery@reisigandtaylorcontemporary.com

____

____

spleen iiiii. July 27 - September 7, 2024. Reisig and Taylor Contemporary is announcing spleen iiiii, a group exhibition built by Allison Arkush, Maccabee Shelley, Luc Trahand, Sinclair Vicisitud. This is the first exhibition at the gallery’s new location in West Adams, and is, in part, positioned to address the space (and time) of the gallery itself as a swappable, interchangeable, permutational, recursive, and unusual place: a functional obsolescence. But also as a place that actively participates in the production of material histories and irregular economies that are constructed with surrounding populations. Further, and more specifically, as an exhibition working with equal parts “academic” (credentialed) and “outsider” artists, this lateral or non-hierarchal context might be a way of breaking bad habits of splitting intellectual and affective processes along disciplinary or professional borders.

Beginning speculatively, this exhibition presents sculptural, photographic, installational, textual, and aural processes working-through questions of obsolescence and displaced or repeated (or forgotten) functions. These questions might include: How do paces or speeds of cultural and industrial production—or making things ourselves—prohibitively reproduce bodily and social relations as consumable, ‘done,’ regular, normal, forms of life and death? How might a (relational) work of art disrupt this economic predetermination of how I (do not) connect to others and objects? And what is at stake in a gallery ‘display’ that takes the relations bound-up in artwork as its primary context? Where and when does an artwork, or the exhibition (or the gallery) for that matter, actually take-place? Or, to borrow a phrase from one of the artists (Shelley), when is the “moment of maximum information”?

Circulating through found (discarded, surplus, or obsolete) objects or materials and various approaches to deforming their ordinary uses or memories, the exhibition works to decipher “readymade” un/realities buried in relations between texts, technologies, furniture, shelters, items, devices images, materials, languages, storefronts, and sounds. These disruptions of a system’s apparent integrity call on anxieties along the loss of functionality (like a technology taken for granted until it’s broken or dysfunctional). Once a usual function is disrupted, it often becomes impossible to decide where something begins or ends, and whether it is inside or outside (its own systems)—or both at the same time (is a hard-drive ‘finished’ or ‘over’ if it doesn’t remember, or is it forgetting to be something else?). Like an organ that has as its function to operate outside the body, or as the possibility of a hole—the removal of a part from a whole—without total destruction. …Broken records and forgetful functions….

A lack of cause creates a hole: like the removal of a spleen. (And then the hole takes the place of the cause, as with an unfound trauma.) But what about the lack of a function? Not the function of the (art) object, which is long gone, but the function of a relation to an object or an other. Or a functional relation that only works to forget how it is used. The function of forgetting—the production of a lapse. Is this also a cause?

Circling the drain of any desire to make sense of something produced and displayed, the exhibition swirls around problems of illegibility, dysfunction, dis/information, and overrepresentation (like this text you are currently reading (or avoiding)). Of something past its time but still future (to the present)….

….

As a(n unnecessary) organ of the human body and a peculiarly usurped modern term, “spleen” came to be associated with aesthetic currents of melancholia, disgust, dissatisfaction, ineffectuality—and the sense of the loss or the lack of a cause (after the poet (and art critic) Charles Baudelaire bandied it around for a bit before the 20th century[1]). Prior, or since the Greek coinage of the root word of ‘spleen,’ ‘splēn,’ spleen—the splenic or splenetic—has designated the (cause of) bad temper. More recently, as artist/writer/dealer John Kelsey writes in “Next-Level Spleen” (published in 2011 in Artforum),

Baudelairean spleen—or disgust as a poetic channel—was always connected to an idea of modern beauty, was maybe even its preferred medium. Any channeling of beauty today would have to occur in relation to crisis and the sublime of viral insecurity. The outmoding of the studio and possibly even of the artist herself, as we deliver our human capacities over to network speed, provides the strange new conditions under which any coming aesthetics must emerge. So we will have to make poetry of the fact that language does not survive speed.[2]

This “fact that language does not survive speed” is immediately evident in the language of art historical/theoretical and philosophical discourses themselves: it is as if each time there is a ‘post-’ (or a ‘non-’ or an ‘anti-’) added to an academic term it is only capable of signaling somewhere, sometime, we cannot quite manage to keep pace with. Post-structuralism, post-modernism… post-studio, post-relational… each a kind of placeholder for some place we have already gone, but might not be capable of going-to. (Is there something unavoidably obsolete about art—and its subjects, theories, histories, and discourses—itself?)

But if this symptomatic ‘post-’ only points to the problem, how does “poetry” attempt to repair a language’s relationship with time? Poetry already operates at the limits of language’s functioning, so what of this lack and lag between the structure of a language or a code and the rate of its reproduction (and the speed of whoever speaks)? Does the poetry account for lost time? How to “make poetry” of this hole? (…Especially if I have already arrived at a place where it is impossible to keep-up (like a spleen attempting to become a liver or a heart, or trying to recover the obsolete body that once needed it—or like a chair trying to take the place of a fence…[3]).) If modern spleen is all about disgust, the lack of a cause, and a kind of listlessness, then contemporary spleen (spleen iiiii)—if I follow the ‘afterward’ propulsion put in place by all these ‘post-’ prefixes—arrives at its poetry along the ‘other end’ of this disposition: the lack of a determined function (or result), and almost too much cause (with all the little technics and systems underlying and overriding the gallery and the works). Too much time eventually becomes not enough memory and forgetting creates a lag that a language cannot keep pace with. If poetry accounts for this discrepancy, is there also a kind of ‘new science’ at work in realizing poetics as a structural repair to these splits between body, language, time, and function? I think this would be a poetics of relation[4] that also shares itself as a functional method and technique, and not just a liberatory horizon and dangerous condition.

Like an obsolete technology that is already-made but is no longer necessary, a human body begins with a spleen but does not need to remain part of it—it can be removed and displaced, turning it from part to (w)hole. (Am I removing the body or the spleen? There is a relativity here.) It seems that, even as a language becomes obsolete, or unable to keep-up with its own presence, the obsolescence itself takes-on its own kind of functioning at this place of disfunction or discontinuity. A non-relation begins to be the precise place where relations are produced (this is perhaps most obvious when social media is taken as an example: each virtual relationship or ‘hyper’ social is generated by the disappearance or disconnection of an actual relation (between bodies)). This is a starting-point of the exhibition: bringing-out relations produced by holes, disconnections, disruptions, and imaginations (or fantasies). And demonstrating the ways in which the recursive, partial, or divergent languages of the works can still be written, read, and lived-out. Despite their erratic features and their resistances to habitual forms of bodies and objects, each of the exhibiting works is produced through complex, systematic methods and techniques that may be read, interpreted, and learned. (For example, Arkush and Shelley use casting processes that catch-hold of both the exactitudes and the errancies or aberrations of their respective techniques, while the collaborative works by Trahand and Vicisitud work with a complex coding of a Max MSP architecture operating the sound-components.)

This timewarped insistence on drifting techniques of reading, writing, and decoding—and learning non/knowledge—is one of the reasons why textual and literary works are noticeably present: to remind me to read. (And to remind me of its impossibility.) But this is also because literature has, in many ways, already realized some of the features of the ‘post-’ art and the ‘post-’ gallery. If the work of art and artists are increasingly ‘outside’ the artwork, the gallery, and the institution (though, surely, this is up for debate…), then what does it mean to bring a literary act into the space of a gallery? (After all, anyone (but not everyone) might access a text even if they cannot read—and they might produce text without having a coherent grasp of the language they are using (TDLR[5]).)

My initial response to this question focuses on the literal, more than the literary. Increasingly, artworks attempt to catch-hold-of and literalize the relations that make-up the work of art. To see the letters that make-up the word (“artwork”). My literal approach to “spleen”—accounting for the (lack of) force of its bio-materiality as an organ or body part as much as a metaphor or modern trope—mirrors the ‘post-relational’ moment of the literalization of the work of art in terms of the artist as interstitial and itinerant, and in terms of the artwork as an interlocutor processing information and producing relations. At least sometimes, the contemporary post-relational artwork forms an attempt to literalize the relations—from the material to the conceptual—of the work of art. (The function of the artist and the artwork occurs as sequences of dis/connection.) Maybe what an aftermath of relational aesthetics looks like is this accounting of relations on ‘all levels’ of a body and the object or instance it encounters and endures, without reducing the relational to the social-political…. A sort of sacrilegious hagiography of persons and things—and the deconstruction of their exceptions or residues.

Unlike (previous) post-relational splenetics, these artworks offer the spleen as a way into and out of a body in a recursive part-whole circulation capable of sustaining the disassembled, tendrilled, auratic/erratic posthuman connections that make-up the un/livable body of today. In other words, the artists and artworks are not just performative citations on dis/connection (caused by technological and social disaffections), but also livable life-and-death-forms that offer ways of going-on that are already possible but not adequately recognized. After all, Baudelaire forgot that the spleen is an organ, not a condition. Its function doesn’t make us sick, but it’s dysfunction does—until its removal.

Ultimately and initially, spleen (in all its iterations: iiiii), provides an envoy into problems of defining/drawing relations (of an object, body, image, organ) based on function: or locating the borders, boundaries, or limits of an entity (body or organ, whole or part—we don’t know yet!) based on its use or dys/functionality. For example, a spleen is an organ—a part (and a “removable” part at that)—only because we know what it is. Its relation as ‘part of a body,’ and thus as an organ, is designed by its known function. But what about its unknown or unknowable functions? Of course, especially since it is not a crafted tool but an organic part, it could be used for anything. For food. For a pillow. For a coin purse. A bricoleur, a ‘handyman,’ makes (m)any uses of a spleen, under the right circumstances. So what happens when the function or use changes? Does the relative status of the entity also change? Is it still an organ? Still a part? Or a (w)hole? The exhibition pushes the lack of the cause to these questions of how a function overtakes and overrepresents the status of an entity (or body) and (intentionally and accidentally and incidentally) designs the limits of this body and its possible relations or transformations—really, permutations—based on this imagination and figure (of Man). (What does a figure have to do with a body, anyway?) Initially and ultimately, a body is constructed based on master tropes that are regulated and enforced through colonial structures.

And someone might be reminded of something like a colonial structure, or maybe its detritus, as soon as someone enters the gallery and is confronted by a haphazard shelter—a broken booth, an uninhabitable hut—with a shattered doorway impossible to open; a technological device I will barely recognize and will not be able to use; and a chair I cannot sit on (while its guarded by the ghost of a fence). I am barred but already inside…. The booth or hut is a kind of little colonial-industrial-complex contained within itself. A booth is mechanical and guard like, regulating entries and exits. A hut is considered primitive and pre-colonial, something not-yet contained by a city of letters. A place where bodies are about to be written and read, already bought and sold. (Either bodies without organs, or organs without bodies: a removed exchange.) Swapped.

It’s like a house but only for a lagging moment. A stall. It conforms to a ‘regular’ human body but also rejects it: I can’t possibly stay for too long. Maybe this demonstrates an Overrepresentation of a Human Body, and reminds the construction of disability through conformative use-designs like chairs, houses, etc…. These spaces conform to a body—actually they themselves form a body as soon as they address someone—but what kind of body? How is a body repeatedly reconstructed through ingrained and educated and disciplined habits? These are not questions of what is (re)produced, but, rather, questions of the rate of (re)production.

<<[…] These intestines, these hoarded organs like my

small bladder,

gallbladder

and

spleen

have been decentralized

A cultural industry, without much esoteric necessity. […]>>

{Excerpt from P. I. G. by Sinclair Vicisitud (incorporated in the installation of boothboothboothboothboothbooth (2024), built in collaboration with Luc Trahand).}

Hopefully, or at least antagonistically, a careful examination of these forgotten functions and broken records offers opportunities for overcoming overdetermined capitalist realisms[6] and the overrepresentation, of (the Vitruvian figure as the body of) Man.[7] It’s not over yet.

But I will never be able to keep-up.

….

Preliminary Materials for a possible press release:

The spleen is a surplus organ that can be removed and the body may lack and continue living without causing much change to the quality of life. Other removable non-vital organs that do not—usually—result in chronic complications of the body’s ordinary anatomical functioning include the gallbladder, the appendix, and the tonsils (among (probably) others—and others that may even be added to body with causing much of a disturbance…). Certainly, there are other organs that may be removed from the body in order to repair a dysfunction or to stop the spread of a disease; however, the removal of these semi-vital organs results in varying degrees of change to a body’s anatomical function or a person’s quality of life.

A spleen (and by its lettered numbering—“iiiii”—we might indicate that it’s already a spare)—is ambivalent to the body it inhabits. It’s one of those atavistic or algebraic residues where we are left with some vestigial limb (like a tail), or in this case some vestige of an organ’s necessary function. A function that only works to forget how it’s used. A forgetful function. An organ-ic obsolescence.

This forgetful, atavistic status of spleen suggests a disconnection between body and time (material and transformation), where a body is always trying to keep-up with its own metamorphoses. Like the failure of language to keep-up with the speed of dis/connection. And also a kind of disæffection or disgust, an abject relation; or, a relation built with irrelations and non-relations—a shoving-off that only brings me closer to what I push-away.

But a functional forgetting also fails to remember its cause, not only its uses, effects, results, or communications. A forgetting punctures the surface sewn-on with the smooth continuity between an organ, an object, or a part and its wholes. And its holes.

What is part? What is a (w)hole?

What is lack? What is a surplus?

How are relations and circulations produced—written, read, and settled—through surpluses, lacks, and displacements?

Why do I determine “quality of life” based on function?

__________

[1] Baudelaire refers to spleen in his poetry in his (1869) collection of short prose poems, title Le Spleen de Paris [Paris Spleen]. Earlier, in his (1857) volume of poems titled Les Fleurs du mal [Flowers of Evil], Baudelaire includes four poems in chapter called “spleen.” (The fact that he stopped at four is why I begin with five, iiiii.)

[2] John Kelsey, “Next-Level Spleen” (Artforum, 2011) {https://www.artforum.com/features/next-level-spleen-200804/}. [Italics added for emphasis.]

[3] Here I am referring to a work by Allison Arkush included in the exhibition.

[4] See Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (Ann Arbor: Michigan Press, 1990).

[5] “Too Long, Didn’t Read.”

[6] See Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (John Hunt Publishing, 2009).

[7] See Sylvia Wynter, "Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument," CR: The New Centennial Review no. 3 (2003): 257.

____________________

Bios

:

Interdisciplinary artist Allison Arkush engages a wide range of materials, modalities, and research in her practice. Her sculptural works can be understood (i.e. read) similarly to her poems, handwritten diagrams, annotations, and even the scrawled lists. But instead of words the arrangements are primarily of physical objects and materials: her more-than-linguistic language. Her approach facilitates the probing exploration of prevailing value systems through a flattening of hierarchies among and between humans, the other-than-human, and the inanimate. Her work meditates on and Venn-diagrams decay and growth, contradiction and harmony, things forsaken and sacred, the traumatic and nostalgic…

Allison Arkush was born and raised in Los Angeles, California. She received her BA in studio art and psychology from New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study, graduating magna cum laude. In 2019 Arkush relocated to Lincoln, Nebraska to begin her graduate studies at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. After receiving her Masters Degree in ceramics and sculpture she continued to teach at UNL until returning to Los Angeles in 2023. Since moving back she has settled her practice into a studio located downtown in the thrumming Fashion District. She has exhibited work at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Art, Baltimore Clayworks, the Eisentrager-Howard Gallery, Turbine Flats, La Bodega Gallery, and Reisig and Taylor Contemporary.

|

Born in Los Angeles, Maccabee Shelley studied environmental and Earth sciences before earning degrees in studio art and ceramics. Intrigued by the perception and projection of value and obsolescence, Maccabee translates refuse through various materials and processes exploring the space between object, image, and experience.

|

French-American interdisciplinary artist Luc Trahand’s work spans multiple mediums and forms from music and sound to language, film, and movement.

|

Sinclair Vicisitud is a (born-and-raised) Los Angeles artist. Working in mixed-techniques and mixed-media, Vicisitud’s figural, expressive work usually takes-place through a practice of painting that interweaves gestural imprints and studied forms. However, this surface-process is often navigated through the multi-dimensional, sculptural features of the canvas or frame. At times, their (initially) painterly work is totally transformed into a sculptural object.

________________________________________

Epilogue:

A Scribble, A Spiral. Gravel and Ground. (Or, Mud, Salt Crystals, Rocks, Water.)

Mud, Salt Crystals, Rocks, Water.

Robert Smithson’s film Spiral Jetty (1970: 36-minute duration).[1] Emerging as a core work of the Land Art movement, this particular piece exemplifies a macho-industrial tendency of the (white, masculine) artists of this movement to consider “Land Art” as a kind of brute—‘boys-playing-with-trucks’—attitude toward “land” (art) as that which bears the mark of development, construction, colonization, and civilization. Something is moved, built, or destroyed. A mark (a scar) remains as a the signature of an unauthorized author: a manifest destiny, made manifest (…an especially topical statement when one considers Land Art’s coinciding obsession with the transformation of natural landscapes throughout ‘the American West’).

According to the informational text provided by the Holt/Smithson Foundation: the “Spiral Jetty is made from over six thousand tons of black basalt rocks and earth collected from the site, Spiral Jetty stretches 1,500 feet long and 15 feet wide in a counterclockwise spiral.” (The work is located on the northeastern shore of the Great Salt Lake.) In part, the film Spiral Jetty functions as a documentation of the work; however, it also aspires to materialize the space-time of the structure through a myth-making genesis: destruction, construction, reconstruction (as the visual and oral narrative articulated through the film).

<<Spiral Jetty is a discontinuous narrative, part science fiction, part document, part travelogue. On the soundtrack Smithson describes “the earth’s history seems at times like a story recorded in a book each page of which is torn into small pieces. Many of the pages and some of the pieces of each page are missing.” He described that the film set out to make this “fact” material>> (Holt/Smithson Foundation).

Working-through the materiality of missing pages and absent information—of (d)rifts, gaps, and lacunas—the screening of this nearly obsolete (or at least already eroding) artwork and its documentation is presented in consideration of the exhibition’s questions of the pace of technology, time, obsolescence, and (dis)appearance: or the inability of any structure, mark, or (recorded) process to keep-up with the rate of its (re)production. Of winding, and becoming unwound—scribbling or spiraling, or stuttering. (This relationship of a sign(al), imprint, or trace to lag and latency is perhaps made more visible by looking at this film as a work that collapses the distance between the event of an artwork’s production and its eventual documentation. Between an event, a memory, and its re-membering: a film.) How does an artwork speak, read, and write its own structure and language? How does a context or document contaminate, reinforce, delay, or survive an artwork? And why is destruction and pollution the usual modes of producing cultural works intended to last? While the film might bring-up these questions, it also demonstrates the different materialities of a work that occur in the gaps and lacunas of its making or presentation—after all, this is where these questions emerge. (Between material, language, and time: or, the loss and recovery of a mark.)

Mud, Salt Crystals, Rocks, Water.

Meanwhile in Utah: as the Great Salt Lake currently dries-up due to climate change (or however else you don’t want me to describe some anthropomorphic consequences of our industrial actions), leaving the Spiral Jetty high-and-dry, there is a moribund opportunity to return to a reflection on the place of ‘environment’ as medium. (Mud, Salt Crystals, Rocks, Water.) As it was originally being made the Spiral Jetty was already acknowledged as a harmful, masculinist intrusion on the natural landscape of the Great Salt Lake—so where does it strand itself now as an intrusive monument to an altered landscape (‘development’) in a place already beginning to end?[2] Hopefully, the film might be posed as a negative didactic in response to this question.

Ultimately and initially, the combination of these events—the performance and the screening—finds dis/connections between performance, exhibition (or display), record (or document), and the pace of presentation (on any of these ‘levels’ or modes). As each of these modes play crucial and recurring roles in the cultural production of art practices, spaces, and institutions—and are particularly central to this exhibition to the extent that it asks about the obsolescence or latency of how art itself constructs its discourses—it seems a relevant place to start to reflect on the beginning of the exhibition’s end. How do I keep-up (with) something I cannot keep?

Mud, Salt Crystals, Rocks, Water.

….

Aftermath

Some Questions: How is something made (or altered)? And how is it made to last (or not)?… What is the scale of memory?

Some Ingredients: A scribble, a spiral (chair, jetty); a shelter, a tract; debris, gravel. Mud, Salt Crystals, Rocks, Water.

Some Processes: Material, Displacement, Building, Duration, Erosion… Forgetting. Mud, Salt Crystals, Rocks, Water.

Some Results: A (dry) Jetty, a Fence-Anchored Chair; a Repeating Language that’s never the same; a Sunset (and sunstroke). Mud, Salt Crystals, Rocks, Water.

(The repetition is enough to assume the machinery.)

….

Before: The Event

<<…less less, in medias res….>>[3]

….

Blizzard, then Heatwave—Screen Memories

Spiral Jetty was one of the first art films I saw during my undergraduate studio arts education. We watched the film in a January-term (3-week intensive) Winter course equipped with an immersive, materially and experimentally driven curriculum gathered under the question of Art in the Ecozoic Era. Partially or initially inspired by an article (1992) by Thomas Berry with the same name, the focus of the course was to turn to the question of the Earth in relation to artwork. Though, perhaps more forcefully, it positioned a way of re-examining the periods of art history in relation to deeper time organized around transformations and industrializations of the Earth through anthropomorphic and anthropogenic processes. So it also posed critical questions about how art is recognized, recorded, categorized, contextualized, and historicized: documented.

Since the course was taught at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts during the middle of a particularly wintery winter, the practices we were able to come-up with were mostly based around the problem of a lack of natural resources aside from ice and snow—and whatever remaining plant life managed to surface (everything else had been covered by a blizzard at the beginning of the term). We were only able to build using materials available outdoors, on the premises of the college. Most students struggled to make anything at all. Many made nothing. My friend from Texas was hospitalized with hypothermia. Our relations to the “Earth” were met with resistances. We were nearly starved-out of making. This course is how I became interested in Land Art, and its consequences—and its aberrations. …. Anyway, my copy of the Spiral Jetty is from that course: nobody wanted it.

And now I have watched this film during a heatwave in Los Angeles. It is never a comfortable screening. First I was too cold, now I am too hot: sunstroked. (—Z80.)

____________________

[1] This film was screened at the closing reception for spleen iiiii (Saturday, September 7, 2024).

[2] It is worth noting the dispute over the upkeep and conversation Spiral Jetty. Smithson himself insisted that the work not be maintained, but once it fell under the custodianship of the Dia Art Foundation, Smithson’s request was ignored and the work has since been conserved. Does the work need to last to continue to work? Does the work need to last to maintain some sort of financialized status (“yes”)? If that is the case, is i the work that’s being maintained or the economy—the market—the work has produced?

[3] This line is a citation of a line recited by Luc Trahand in his performance of Humdrum at the closing reception for spleen iiiii (Saturday, September 7, 2024).

________________________________________

Supplements:

..

o.

Humdrum (Sound/Text Installation) Statement by Luc Trahand*

<<Within the contrived apotheosis of the white gallery, the echolalias recall the rhythms of the heart—”l’organe amoureux de la répétition.”[1] While the ruptured spleen weakens, the infections of thought can propagate. What starts as nested addition and subtraction becomes a palimpsestic, immersing monologism that is unequaled. A paradox underlies experience: the belief of reality. Architects of our incarceration, bound to an incalculable entropy, one decides what cell to walk into, and, unfreely willing, locks the door. Comfort washes over as one learns the square inches of crusty cement flooring and plastered wall, gradually coloring in the complete unknowns with vacuous understandings. To these constructed confines venerated, our appraisal rings, inebriated by sweet no-things.>>

_

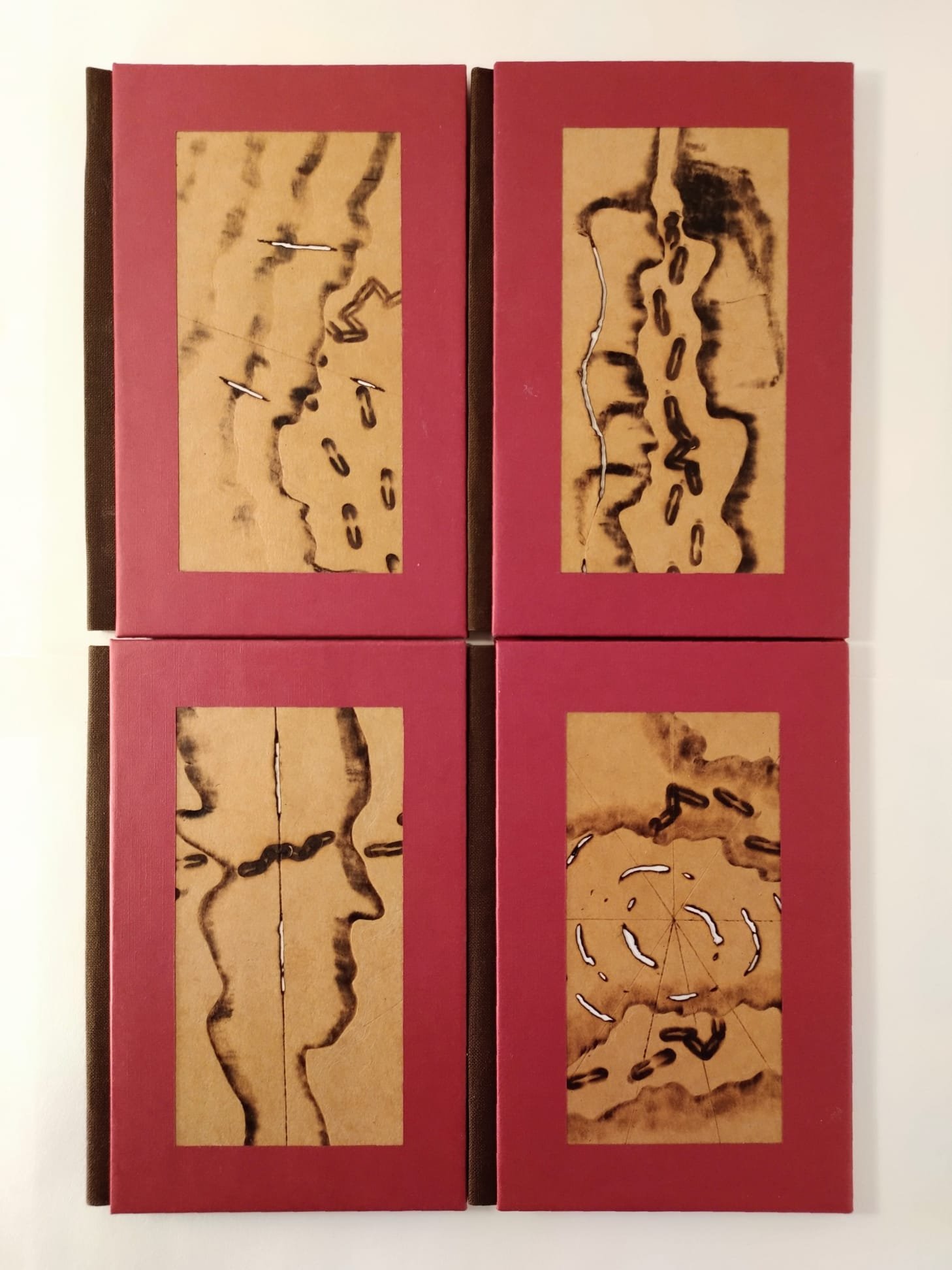

Hum•drum refers to Trahand’s textworks (books) and correlative soundworks included in the collaborative installation works (built with Sinclair Vicisitud) incorporated in this exhibition. (It also refers to the performance (at the exhibition’s Closing Reception) rendered as an extension—a reading—of this work.) Detailing the work, Trahand writes <<With the aim of decorticating the layers of summation to expose the skeleton of our realities, phrases were arranged through a stochastic process to be ordered differently in each printed copy. Using the software Max/MSP to code probabilities and random variables, obtaining degrees of unpredictability forces the reader/listener to consider the operations that they are making while building an understanding of the work. The primary focus becomes the relations between phrases and between paragraphs rather than the ensuing narrative. [] The same stochastic model used to order the phrases is synchronously creating the adjoining sound element of this work. It is therefore also different per printed copy. An underlying bed of sine and triangle waves oscillate at flipped 180º phases and at varyingly small differences of frequency (heard as low accelerating and decelerating pulses) which emphasize the subtraction between the elements. Above this sonic stratus, clouds of languishing violins come and go, like voiceless, indiscernible echoes. In this midst, the rusty churn of a trudging cello chases an antsy, effervescent saxophone. The latter acts as our mind does on our perceptions—it yearns for legibility and won't shy away from lying to conform. The whole soundscape is a tethered subordinate to the hand that writes, a rhythmic dictator that we must revolt against, but that we cannot and will not survive.>>

*{Hum•drum installation statement; link to project. Images of books courtesy of the artist.}

____________________

[1] Gilles Deleuze, Différence et Répétition.

_____________________________

Installation View\Day [Sunny] (0) | spleen iiiii | Allison Arkush, Maccabee Shelley, Luc Trahand, Sinclair Vicisitud. July 27 - September 7, 2024.

(1)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6)

(2)

(7)

(8)

Luc Trahand. boothboothboothbooth. 2024. Found wood, chain, pyrography &chalk, electronics: Behringer Dynamic Microphone, Arduino Uno R3 Microcontroller (coded using Arduino IDE), Bass Shaker 50W, Aiyima Amps 160W, UART Control Serial Music Player Module, HC-SR04 Ultrasonic Sensor Module. (Booth Installation constructed in collaboration with Sinclair Vicisitud.) Approx. 4 x 4 x 6 feet.

Luc Trahand. boothboothboothbooth. 2024.

Luc Trahand. boothboothboothbooth. 2024. [Detail.]

Luc Trahand. boothboothboothbooth. 2024.

Luc Trahand. boothboothboothbooth. 2024. Placed: Humdrum. Edition 1 of 5. Book.

Luc Trahand. bodybody. 2024. Metal door sheet, foam, concrete, plaster, shellac, wood stain, coffee. [Installed with steel chain.] Approx. 6 x 1 x 2 feet.

Luc Trahand. bodybody. 2024. [Detail.]

Luc Trahand. bodybody. 2024.

Luc Trahand. bodybody. 2024. [Detail.]

Luc Trahand. bodybody. 2024. [Detail.]

Luc Trahand. Untitled Component of Luc Trahand and Sinclair Vicisitud. boothboothboothboothboothbooth. 2024. Placed: Humdrum. Edition 3 of 5. Book.

Luc Trahand. Untitled Component of Luc Trahand and Sinclair Vicisitud. boothboothboothboothboothbooth. 2024. Placed: Humdrum. Edition 3 of 5. Book.

Luc Trahand. Humdrum. Edit 3 of 5. Book. [Open: pages 11-12.]

View of the Max/MSP patch (by Luc Trahand) that stochastically renders the organization of the phrases in the Humdrum textworks, and synchronously correlates these phrases to the architecture of the soundworks. (Courtesy of the artist.)

Allison Arkush. Spiral Notebook Tablet. 2016. Stoneware with slip, aluminum wire. 6.25 x 10.25 x 7.5 inches.

Allison Arkush. Spiral Notebook Tablet. 2016. {Detail.}

Luc Trahand and Sinclair Vicisitud. boothboothboothboothboothbooth. 2024. Found wood, found bedside table, pyrography, chalk, (carcasses: metal structure, canvas cloth, plaster, spray paint, chain, chair legs), electronics: Behringer Dynamic Microphone, Arduino Uno R3 Microcontroller (coded using Arduino IDE), Bass Shaker 50W, Aiyima Amps 160W, UART Control Serial Music Player Module, HC-SR04 Ultrasonic Sensor Module. Approx. 8x4x5 feet.

Luc Trahand and Sinclair Vicisitud. boothboothboothboothboothbooth. 2024. {Looking-in.}

Luc Trahand and Sinclair Vicisitud. boothboothboothboothboothbooth. 2024. {Looking-down.}

Luc Trahand and Sinclair Vicisitud. boothboothboothboothboothbooth. 2024. {Detail.}

Maccabee Shelley. Memory. 2024. Cast glass and electronics (Hard Disk Drive).

Maccabee Shelley. Memory. 2024.

Maccabee Shelley. Memory. 2024. [Morning light.]

Maccabee Shelley. Memory. 2024. [Morning light.]

Maccabee Shelley. Memory. 2024.

Allison Arkush. Basket Assemblage. 2021. Earthenware tile with terra sigillata, epoxy clay, insulated copper wire, waxed linen thread. 6 x 4 x 4.5 inches.

Allison Arkush. Basket Assemblage. 2021.

Allison Arkush. Fence Anchored Chair-Mauve, with Detached Corner. 2024. Found rolling chair, hydrocal, gravel, dried plant (unidentified species). 14 x 33 x 30 inches.

Allison Arkush. Fence Anchored Chair-Mauve, with Detached Corner. 2024.

Allison Arkush. Fence Anchored Chair-Mauve, with Detached Corner. 2024.

Allison Arkush. Fence Anchored Chair-Mauve, with Detached Corner. 2024.

Allison Arkush. {Left} Buddy Vase-Light. 2021. Glazed ceramic, epoxy clay, hemp rope, dried plant (unidentified species). {Right} Buddy Vase-Dark. 2021. Glazed ceramic, unfired clay, hemp rope, dried plant (unidentified species). 3 x 3 x 5 inches each.

Allison Arkush. {Left} Buddy Vase-Light. 2021. {Right} Buddy Vase-Dark. 2021.

Allison Arkush. Buddy Vase-Dark. 2021. [Detail; dead weed from gallery premises.]

Allison Arkush. Fence Anchored Chair-Mauve, with Detached Corner. 2024.

Works by Allison Arkush.

Allison Arkush. String Figure for DH. 2022. Porcelain casting slip, encaustic medium, hemp rope, copper tube. 15 x 19 x 2 inches.

Allison Arkush. String Figure for DH. 2022.

Allison Arkush. String Figure for DH. 2022. [Detail.]

Works by Luc Trahand.

Luc Trahand. boothbooth. 2024. Found wood, curtain, canvas dropcloth, pyrography & chalk, electronics: Behringer Dynamic Microphone, Arduino Uno R3 Microcontroller (coded using Arduino IDE), Bass Shaker 50W, Aiyima Amps 160W, UART Control Serial Music Player Module, HC-SR04 Ultrasonic Sensor Module. (Booth Installation constructed in collaboration with Sinclair Vicisitud.) Approx.10 x 3 x 3 feet.

Luc Trahand. boothbooth. 2024. {Outside} [Detail.]

Luc Trahand. boothbooth. 2024. {Inside.}

Luc Trahand. boothbooth. 2024. {Inside.} [Detail.]

Luc Trahand. boothbooth. 2024. {Inside.} Placed: Humdrum. Edition 2 of 5. Book.

Luc Trahand. bodybodybodybody. 2024. Metal door sheet, foam, concrete, plaster, shellac, canvas cloth, epoxy resin. Approx. 6 x 3 x 2 feet.

Luc Trahand. bodybodybodybody. 2024. {Others in background.}

Works by Allison Arkush.

Allison Arkush. Fence Anchored Chair-Mauve: Detached Corner. 2024. Found rolling chair, hydrocal, gravel, dried plant (unidentified species). 14 x 33 x 30 inches.

Allison Arkush. Fence Anchored Chair-Floral. 2024.

Allison Arkush. Fence Anchored Chair-Floral. 2024. {Detached corner from "Fence Anchored Chair-Mauve behind.}

Allison Arkush. Fence Anchored Chair-Floral. 2024. {Detached corner from "Fence Anchored Chair-Mauve behind.}

Allison Arkush. Fence Anchored Chair-Floral. 2024.

Allison Arkush. Fence Anchored Chair-Floral. 2024. Childhood rolling chair, hydrocal. 35 x26 x27 inches, not including scribble. {Others in background.}

Works by Maccabee Shelley. Day.

Works by Maccabee Shelley. Day.

Works by Maccabee Shelley. Day.

Maccabee Shelley. From the Obsolescence series. 2019. Digital Photography, long exposure [projection]. Day.

Maccabee Shelley. From the Obsolescence series. 2019. [Projection.]

Maccabee Shelley. End of the Line. 2024. Cast glass and electronics (answering machine). 4 x 5 x 4 inches. [Installed with LED tape-light beneath.]

Maccabee Shelley. End of the Line. 2024.

Maccabee Shelley. End of the Line. 2024.

Maccabee Shelley. End of the Line. 2024.

Maccabee Shelley. End of the Line. 2024.

Maccabee Shelley. End of the Line. 2024. [Detail.]

Maccabee Shelley. End of the Line. 2024. [Detail.]

Sinclair Vicisitud. Reisig's Patio. 2024. Oil on Canvas. 5 x 6 feet. [Detail; light in front.]

Installation View\Night (9) | spleen iiiii | Allison Arkush, Maccabee Shelley, Luc Trahand, Sinclair Vicisitud. July 27 - September 7, 2024.

(10)

(11)

(12)

(13)

(14)

(15)

(16)

(17)

Remnant (0). Exhibition Documentation: Checklist. 8 x 11 Copy Paper in Cast Gelatin with LED light underneath.

Sinclair Vicisitud. Reisigs' Patio. 2024. Oil on Canvas. 5 x 6 feet.

Sinclair Vicisitud. Reisigs' Patio. 2024.

Sinclair Vicisitud. Reisigs' Patio. 2024.

Sinclair Vicisitud. Reisig's Patio. 2024. [Detail (Night).]

(18)

(19)

(20)

(21)

Still [35:52:00] from Robert Smithson’s film “Spiral Jetty” (1970). (This film was screened at the Closing Reception (Saturday, September 7, 2024).)

![Installation View\Day [Sunny] (0) | spleen iiiii | Allison Arkush, Maccabee Shelley, Luc Trahand, Sinclair Vicisitud. July 27 - September 7, 2024.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/37a9e0cd-ad74-4efb-b1a8-ec4386854559/install+1.jpg)

![Luc Trahand. boothboothboothbooth. 2024. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/f58ba4db-7a07-45f8-8cd4-288e34bffcd8/LT+6.jpg)

![Luc Trahand. bodybody. 2024. Metal door sheet, foam, concrete, plaster, shellac, wood stain, coffee. [Installed with steel chain.] Approx. 6 x 1 x 2 feet.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/dca915a7-3c44-41f8-9d74-37fbf54349ac/IMG_3428.jpg)

![Luc Trahand. bodybody. 2024. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/9f4cb206-ad3d-4f60-a600-167377818336/LT+7.jpg)

![Luc Trahand. bodybody. 2024. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/012669e0-88de-41e6-85ad-f729e6d9bd8f/LT+16.jpg)

![Luc Trahand. bodybody. 2024. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/044b73a6-4a37-45e5-a8c3-c17f0afe371c/LT+8.jpg)

![Luc Trahand. Humdrum. Edit 3 of 5. Book. [Open: pages 11-12.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/cdfa484b-ee4b-4cd3-a3e0-81363a5cf075/LT+2.jpg)

![Maccabee Shelley. Memory. 2024. [Morning light.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/4c66530e-e7fb-4441-91fc-b590208d6ab3/MS+16.jpg)

![Maccabee Shelley. Memory. 2024. [Morning light.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/8b9c154d-616f-4e71-bcce-059b983febbb/MS+17.jpg)

![Allison Arkush. Buddy Vase-Dark. 2021. [Detail; dead weed from gallery premises.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/c8d1e59a-ec17-47cb-af39-9e7e7c73a008/AA+1.jpg)

![Allison Arkush. String Figure for DH. 2022. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/afaee282-c442-4088-b3f1-8318eb0a757d/AA.jpg)

![Luc Trahand. boothbooth. 2024. {Outside} [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/90856287-bf50-4eb4-a55f-be0ff0391399/LT+9.jpg)

![Luc Trahand. boothbooth. 2024. {Inside.} [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/26bbb8ea-4a8d-4781-9fd6-6ca0d499d28d/LT+12.jpg)

![Maccabee Shelley. From the Obsolescence series. 2019. Digital Photography, long exposure [projection]. Day.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/346bf0e3-857e-4c1a-8dc5-bded55a66276/MS+13_%3F.jpg)

![Maccabee Shelley. From the Obsolescence series. 2019. [Projection.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/1f517162-bd1b-47ba-b2f1-6ee21bcb20a0/MS+14_%3F.jpg)

![Maccabee Shelley. End of the Line. 2024. Cast glass and electronics (answering machine). 4 x 5 x 4 inches. [Installed with LED tape-light beneath.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/222eb887-9e70-4fe3-bfe7-5f83ac12aad1/MS+2.jpg)

![Maccabee Shelley. End of the Line. 2024. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/f788784f-e839-4cf6-a480-7d7a0997fcc3/MS+10.jpg)

![Maccabee Shelley. End of the Line. 2024. [Detail.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/7e4bd763-a5d0-46b2-b60a-c6638958e2d7/MS+11.jpg)

![Sinclair Vicisitud. Reisig's Patio. 2024. Oil on Canvas. 5 x 6 feet. [Detail; light in front.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/7cb9bb39-b8b3-4cb4-82ae-8cbada2e9064/SV0.jpg)

![Sinclair Vicisitud. Reisig's Patio. 2024. [Detail (Night).]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/da95713d-1214-4117-a9e2-3102309dc18f/SV+7.jpg)

![Still [35:52:00] from Robert Smithson’s film “Spiral Jetty” (1970). (This film was screened at the Closing Reception (Saturday, September 7, 2024).)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/619c221f6addfe04124c8b97/43b59e3d-0cd2-4624-87ad-ce91316adb29/Screenshot+2024-09-08+at+11.04.49%E2%80%AFAM.png)